Being Part of The Great Reshuffle in Rural Middle America

Editor’s note: We first interviewed Edgar Oliveira as part of our report on the diversity of rural America, released in September 2019. Since then, he’s written four blogs for us, including The Force of Civility in Rural Middle America in November 2019; After Business Plunges in the Pandemic, North Dakotan Restaurateur Perseveres, Finds Resilience in September 2020; and Amid North Dakota’s Labor Shortage, Dispelling the Myth that “Nobody Wants to Work” in October 2021. His latest piece is on his career evolution.

Like many places around the country, here in Morton County, North Dakota, (pop. 31,118) the business community has lately been spooked by inflation and gas prices, but the most pressing problem is the ongoing labor shortage. Lack of labor has forced a few businesses to permanently or temporarily close. My neighbors complain, but soldier on. At the same time, there is demand for services, and a few restaurants are slated to open. I’m watching these trends as a catering entrepreneur, even as I take steps toward a new career.

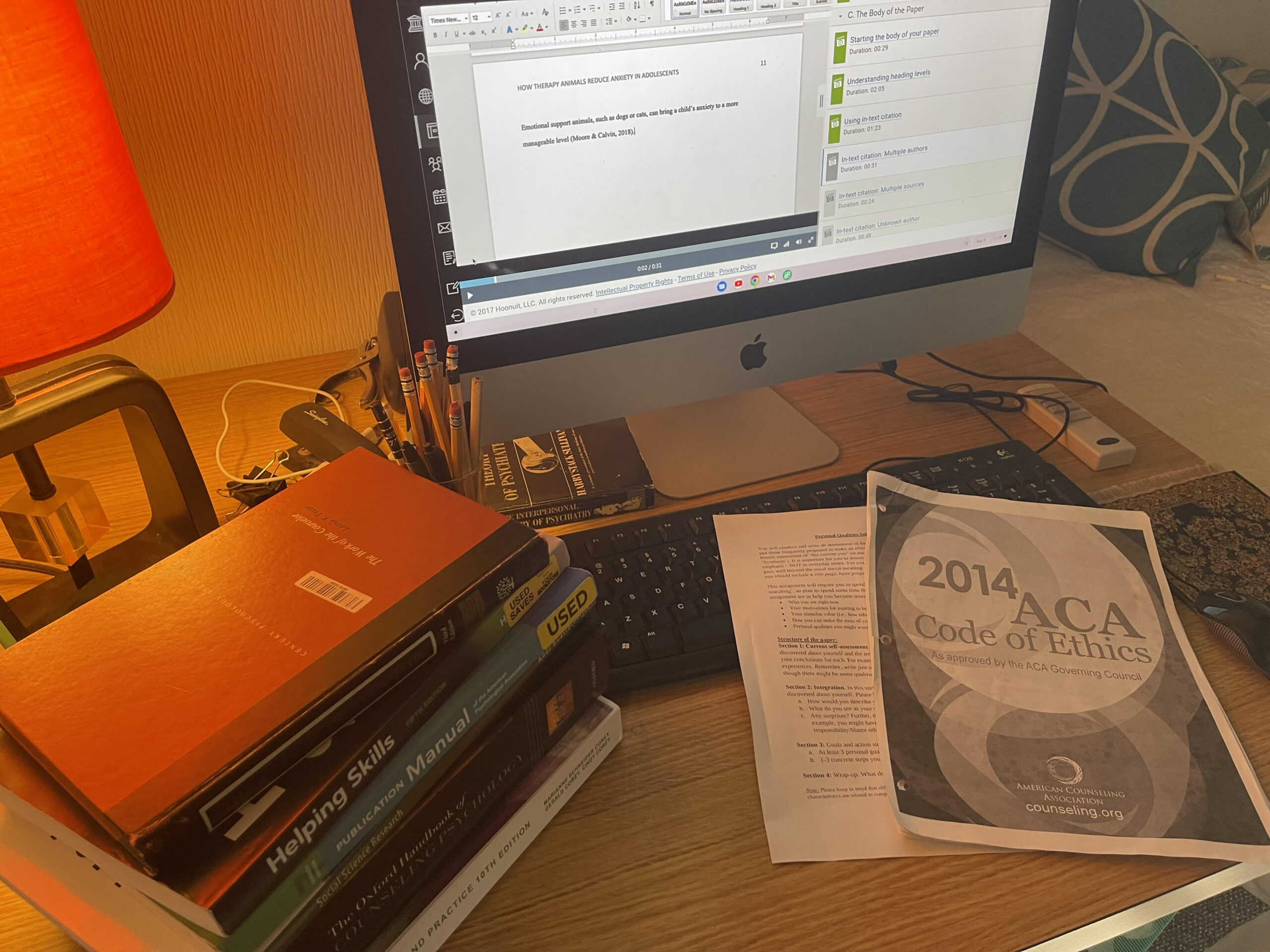

As was true for many Americans, the pandemic made me prioritize my health, well-being, and happiness — and rethink my future. Serving on Morton County’s social service board, I initially considered pursuing social work, but after some deliberation and attending to my actual interests, I’ve chosen to go into counseling. I’m set to graduate with a master’s degree in counseling psychology in fall 2024, three months after I turn 50.

In 1997, I earned bachelor’s degrees in physiology and psychology, and volunteered in a health clinic in Brazil after graduation. Over the years, I stayed interested in psychotherapy and psychology. However, the major contributor to my decision was my last 12 years in the restaurant/food business and my daily brushes with mental health and substance abuse issues.

Yes, working in the food industry is challenging, underappreciated, competitive, and usually poorly paid. The industry’s economic structure makes it so, not the social media caricatures of evil bosses or lazy workers. Systemic changes are unrealistic, so one must accept long hours, a revolving door of kids, and too many burned-out workers.

The grind was unsustainable, and my day-to-day life was filled with conflict, uncertainty, and unhappiness. Most importantly, this environment conflicted with my values of being helpful, fair, and kind. Toward the end and shortly before the pandemic, I experienced depression, further pushing me to change. Lest I sound too negative, I empathize with people who struggle and try to make ends meet. I’ve also worked with rugged, inspirational people in the food industry. My aim has always been to help people struggling, but I’ve never felt I was in a place to do so.

On a whim, I researched a few counseling psychology programs, talked to some alumni, and applied to the University of North Dakota. I wrote my essay, gathered a few letters of recommendation, interviewed, and got accepted. It happened quickly, and it was a much-needed boost of hope. The only person I told was my wife.

Barriers to Going Back

“Anti-college” sentiment is real where I live in Mandan (part of Morton County in Rural Middle America). Part of it is about cost, and part of it relates to the perceived political environment at universities. It’s not uncommon to hear that colleges are “woke” or indoctrinating and are not worth the cost. A prevalent narrative of “not going to college and getting a job” also exists in rural America. Here the unemployment rate is currently low at 2.3%, wages are up, and the recent oil boom further encouraged this thinking. When I tell people I went back to school, I sometimes hear an awkward silence or the incredulous, “Why would you do that!?” Additionally, Bismarck, about 10 minutes away across the river, is not a college town; state universities are some 200 miles away in Fargo and Grand Forks.

Undoubtedly, higher education has changed since I graduated. Yes, the political “vibe” is far more progressive. The criticism of a climate that blunts student engagement is fair. I tend to agree that sometimes divisive and unhelpful interventions are part of the university environment (yes, I’m a liberal). However, increasing awareness of racial or gender prejudices is unequivocally helpful. So is adding pronouns to your email signature (yep, get over it). Knowing how we affect others does not reduce freedom but defies a world determined to disconnect us.

As an older student, I’ve had to deal with new insecurities. Could I absorb the material? Does anyone even use a pencil or a notebook? (I still do.) Would I be able to keep up with my younger classmates? While sometimes it seems the material doesn’t stick, being older improves my ability to focus, organize, and prioritize. I study twice as much if it takes twice as long to learn. Maturity, contrary to my initial anxieties, is an educational asset. My grades are excellent, I am engaged, I constantly think about the material, and I don’t feel others are ahead of me.

There is a genuine concern about cost and the ability to recoup this investment. Counseling psychologists can work well into their later years. My health is good, and I look forward to working well into my later years.

Finally, the online experience can be isolating. I miss the classroom environment, getting to know people, and discussing things. I’ve fought the isolation by reaching out to my teaching assistants and professors and connecting with them via Zoom. They’ve been happy to see me and engage.

Was it worth it?

Yes.

First, this graduate program has asked me to rethink my relationship with what I thought was true. This relationship is becoming simultaneously less rigid and more complex. Deep learning paradoxically illuminates the depths of one’s ignorance. Furthermore, this “knowledgeable ignorance” is freeing me to be more tolerant, accepting, and empathetic. These characteristics are not trivial; they are improving my quality of life.

All of this is to say that my choice has been wise. Counseling psychology asks professionals to introspect, understand cultural and historical influences, be self-aware, patient, and, most importantly, be comfortable in ambiguity. Training to be a counseling psychologist is a profoundly personal experience, and I am grateful and delighted for the opportunity to take this step.

Edgar Oliveira owns and operates Harvest Catering & Events and is a full-time, first-year student in the Master of Counseling program at the University of North Dakota.

Edgar Oliveira owns and operates Harvest Catering & Events and is a full-time, first-year student in the Master of Counseling program at the University of North Dakota.