A South Dakota Community’s Economic Turnaround and Model for Inclusion

Immediately after the near extermination of the Native tribes on the northern plains in the late 19th century, the railroads became kings. Deeded vast swaths of the West by the federal government, the railroads advertised and sold cheap land and access to homesteads to all comers. Americans from farther east and a dizzying mix of northern and eastern Europeans flocked to the siren call of arable land: Germans, Norwegians, Russians, Swedes, Poles, Ukrainians, and Finns; Catholics, Methodists, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Mennonites, and Hutterites. For nearly a century, Huron, South Dakota (pop. 14,263), the county seat of Beadle County (pop. 18,338), part of Rural Middle America, prospered and grew as the “end of the line” for the Chicago and Northwestern Railway.

Situated in east-central South Dakota, this community is part of a collection of places in Rural Middle America and the Aging Farmlands, where corn, soybeans, cattle, and silos appear out to every horizon, punctuated by tiny hamlets with populations that rarely exceed two digits, and a few larger towns with a gas station, a truck repair shop, a few stoplights, churches, and a school. Over the decades, the small American family farm gave way to modern mechanization that upset the farming equation across America. A farmer who might have grown up helping his parents tend a few hundred acres suddenly could not compete without owning or leasing ten-fold that much land. As former South Dakota Governor Harvey Wollman, who grew up on a farm just north of Huron, puts it, “When I grew up in this township, six square miles, there were 24 farms, and I knew all of them. Now there are about four. The land is more productive than ever, but there are vastly fewer farmers.”

In this agricultural landscape, Huron stands out for its social innovation to adapt to a confluence of changes. When conditions deteriorated here, community and elected leaders got to work in the early 2000s to save the town, bringing in new industry and workers. Two decades later, Huron’s multicultural demographics, warm relationships between students, increased enrollment in the schools, and improved retail choices point to a successful model of inclusion. These positive results came because the community has been, and continues to be, all in on the transformation.

Rural Middle America Counties

The Grand Experiment to Save a Town

Beginning in the 1970s, stagnation followed population decline in the town of Huron. As retired school superintendent Terry Nebelsick remembers, “The conditions here in Huron were bad enough to merit a gut check on the town. We lost Huron University, Northwestern Energy, part of the railroad management, and the pork plant. Our houses were worth 40 cents on the dollar. School enrollment dropped from 2,400 in 1997 to 1,800 by 2005. We knew we had to do something, or this town was going to die. In 2004, we secured a new meat processing plant and suddenly we needed a workforce.”

The new turkey processor is a cooperative of 44 independent Hutterite colonies that farm turkeys in North and South Dakota and Minnesota. The new company brought in that workforce from two places: Hispanic workers from Mexico and Central America, and a large group of ethnic Karen (pronounced Kah-REN) refugees who had been living for more than 20 years in refugee camps in Thailand, suffering during ongoing ethnic cleansing by the Myanmar (Burmese) military. Longtime Huron internal medicine doctor and town leader Bob Hohm and his wife, Holly, say the town had experience with bringing in foreign workers. “The first wave was Vietnamese boat people in the late 1970s,” says Bob, an avowed family-values conservative. “They got nothing but respect from the town. They were hard workers and if you are willing to work hard, you are welcome here.”

The rapid influx of thousands of newcomers between 2007 and 2010 created immediate challenges for the community. Former state senator Jim White says he worked with Nebelsick, starting in 2011, to craft a support system to make the transition work for both what White calls the “New Americans” and the traditional white, largely conservative local community. “We needed to fund an English as a Second Language program. We needed to find money in the budget. As part of the state legislative budget process, we took it out of the education budget discussion and sold it as economic development, and we got bipartisan support.”

That budget legislation was introduced in January 2012 by White, a Republican, and Peggy Gibson, a Democrat, and passed the next month with the blessing of Governor Dennis Daugaard. The support by the community led Jack Links Jerky to add capacity to an existing plant near Huron in 2012, adding several hundred new workers, mostly from Central America, and most of whom live in Huron.

Both Wollman and White give much credit to Nebelsick for two critical decisions that made this bold experiment work. “The only institution that practices total agape (unconditional) love, is the public school,” says Nebelsick. “That is our mission. Your parents are broke, your dad’s in prison, your mom is in rehab, you come from a different country with no language skills; we are here. I told the teachers, ‘Look around; this is who we are. Either embrace it or move on.’ Then we saw people selecting schools to keep the new arrivals essentially segregated, so we reorganized around grade-level schools so all kids in the same grades go to the same school. Now these kids from different countries of birth have all gone to school together since kindergarten.” Nebelsick’s changes were big and expensive, and the local bond issue to fund them passed in 2013 on the first attempt with 72% approval.

It Is Working in Huron

Today, roughly 10 years after the turkey processing plant opened, the population of Huron is up 13%, and the schools enroll 3,000 students. New stores like Walmart, Runnings Farm and Hardware Supply, and Slumberland Furniture have opened since 2012. New Americans are arriving from Cambodia and Vietnam as jobs open both in the meat processing plants and with the growth of the town. Today, 60% of the students in the Huron schools are children of color, according to the South Dakota State Report Card, and every person I spoke with rushed to point out that the homecoming royalty in 2022 were all Karen students. The honor roll is packed with Karen and Hispanic kids each year. “The Karen girls are performing academically off the charts,” says Nebelsick. “There are very few problems between students. When kids grow up together, they don’t see color.”

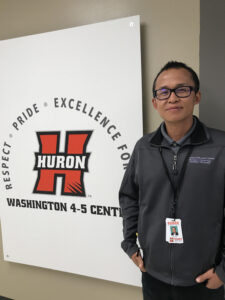

Ethan Moo is Karen and came to Huron 10 years ago after surviving war, starvation, and growing up in a refugee camp. Now he is married with two young boys, and works at the elementary school as a translator, mostly for parents who have not acquired English as fast as their children. “My kids have friends at school who are all races. In elementary school they all play together; they don’t mind what color you are or where your family came from.”

The high school boys’ soccer team, nearly all of whom are Karen or Hispanic, was seeded No. 1 in the state tournament this year. Senior team member Shamui says, “It was kind of hard when we first got here in 2010 getting used to everything. We had clean water and electricity for the first time. The local people were really good to us. The teachers really helped us. We didn’t do anything bad for the people to hate us. We have friends in all of the groups. We’ve hung out with them since we were young. A few of the white kids are mean to us, call us names, but not very many. Our families teach us to just let them talk and not let them get into our heads.”

There is some evidence that the Karen are adapting better than some of the Hispanic students, many of whom are here without a nuclear family. Romana Oliva was born in the United States and both parents were farm workers from Mexico. “We have Hispanic high school students here who are living with a sister, brother, uncle, or cousin who might just be a few years older than they are. And the students have to work as well as go to school to help pay the expenses. Some of the young people are acting as ‘parents’ even though they may only be 19 or 20 years old.”

Holly Hohm recalls that the traditional white community was initially worried because they had heard rumors about crime in immigrant communities in other cities. Nebelsick puts his finger on the exact moment when that concern flipped not only to acceptance but pride in the New Americans. “We have had almost no problems at all with the Karen, but one time around 2016, a few Karen teenagers were caught vandalizing cars. Those families put an article in the local Huron Plainsman paper, writing, ‘Those are our children. They broke every vow we have made to this community. They put us in a situation where you have been so welcoming, you gave us jobs and a chance at America. We beg your forgiveness, we will hold them accountable; we will take care of this.’ It was over: game, set, match.”

Is this model exportable to other rural towns slowly dying because of the dramatic changes in the farm system? The jury is still out. Some families have sent their children to nearby school districts where the population is essentially all white. Sue Gose, a retired teacher who now runs a local thrift shop and food pantry, says, “You would probably hear some different things about immigrants if you hung out in the local bars.”

Meanwhile, Jim White says, “Other communities are recognizing the importance of New Americans to their workforce, but some of them have not followed the model of the community fully welcoming and supporting them. Here in Huron the kids see themselves as friends and brothers and sisters. In those other towns people are still fighting to keep their kids in one school or another. We don’t have that animosity in our community; they do.”

Grant Lichtman, an author and educator, has begun a long, audacious journey in a small RV to understand what wisdom lies in overlooked communities and cultures that we are losing amid the cacophony of news media, social media, political media, and one-minute “influencers” who are paid to be anything but wise. As Lichtman travels along “Wisdom Road," his big question for people he meets is: “What elements of your cultural traditions might help heal the deep divides in our society today?”

Grant Lichtman, an author and educator, has begun a long, audacious journey in a small RV to understand what wisdom lies in overlooked communities and cultures that we are losing amid the cacophony of news media, social media, political media, and one-minute “influencers” who are paid to be anything but wise. As Lichtman travels along “Wisdom Road," his big question for people he meets is: “What elements of your cultural traditions might help heal the deep divides in our society today?”