Breaking Barriers to Connectivity in a Michigan College Town

In the College Town of Ingham County, Lansing resident “Stephen,” an ex-felon, struggles to afford internet at home. He left prison about four months ago and prefers to keep his identity anonymous due to the stigma of being a felon.

As Stephen studies for a couple of IT certifications so he can get a better paying job, he said low wages and part-time work mean he can’t afford a monthly internet subscription at home.

“I have my cell phone, but it’s kind of like navigating the internet in a Sherman tank,” Stephen said. To get online, he goes to a nearby laundromat, library branch, or Michigan Works office. Sometimes he checks out a mobile hotspot from the Capital Area District Library, but those loans only last two weeks.

To address this persistent digital divide, Ingham County is working with 12 other Michigan communities to develop a comprehensive plan. The county commission’s Broadband Task Force began the next stretch of their multiyear project in November.

Part of the task force will spend the next five months examining barriers to internet access, from affordability to device access to cybersecurity. Although Ingham is home to well-connected institutions like the state capitol and Michigan State University, these problems prevent county residents from getting fast, reliable internet at home.

At the end of their review, the task force will have “a long-term digital equity strategy” to give to the county commission. The plan could include recommendations like a signup program for federal money, training for digital navigators, or other community engagement efforts that address the structural barriers that go beyond “wires in the ground.”

Multiple Barriers

Among digital equity scholars and advocates, a common metaphor used to describe internet insecurity is the “three-legged stool” or digital inclusion triangle — infrastructure, devices, and the skills to use them. These are just the tip of the iceberg, said Pierette Renee Dagg, director of technology research at Merit Network.

“When you look through 25 years of research, it really demonstrates that that triangle is where the actual digital equity work starts,” she said. “There are all sorts of issues with structural barriers or limitations on accessible design or culturally relevant training [needed] to be able to understand and make the most of the internet.”

Digital equity is made up of several “ingredients,” according to Sheryl Knox, director of technology at the Capital Area District Library. Larger socioeconomic forces influence who can collect those ingredients and use them to access the internet.

“Unfortunately, a lot of the factors that we see interconnected with the digital divide are things like economic factors, ability to speak English or not, [and] race,” she said. Age is also a factor – skills like digital literacy and digital safety can be major roadblocks for older adults who didn’t grow up using the internet.

“It’s everything beyond the wires in the ground,” she said. Knox is also a member of the task force, which began investigating gaps in internet access in 2022. The task force is applying for federal funding to expand internet infrastructure in the county but is also looking at other factors that have historically been addressed by libraries.

A Local Tradition

Public libraries have been part of digital equity efforts since the 1990s, Knox said.

“Libraries all over this country started carving out spaces in their [buildings] to put computers in and to get Internet connections,” Knox said. Libraries are now known as the one public space with free internet access.

“We’ve added an entire layer of service at libraries that didn’t exist” before, Knox said. As laptop and mobile device use skyrocketed in the 2010s, libraries began providing free wireless internet inside and outside their buildings. Now they loan internet-capable devices and mobile hot spots to patrons, allowing them to take internet access home with them — temporarily.

“All along that way, we’re constantly helping people figure it out,” Knox said. “We are tech support for many people.” One-on-one coaching on how to use devices and the internet can make a huge difference for people struggling to connect, she said.

Federal Help

But the library can’t help patrons pay their internet bills. A federal subsidy program exists to help Americans who qualify, but it is running out of money and isn’t easy to access.

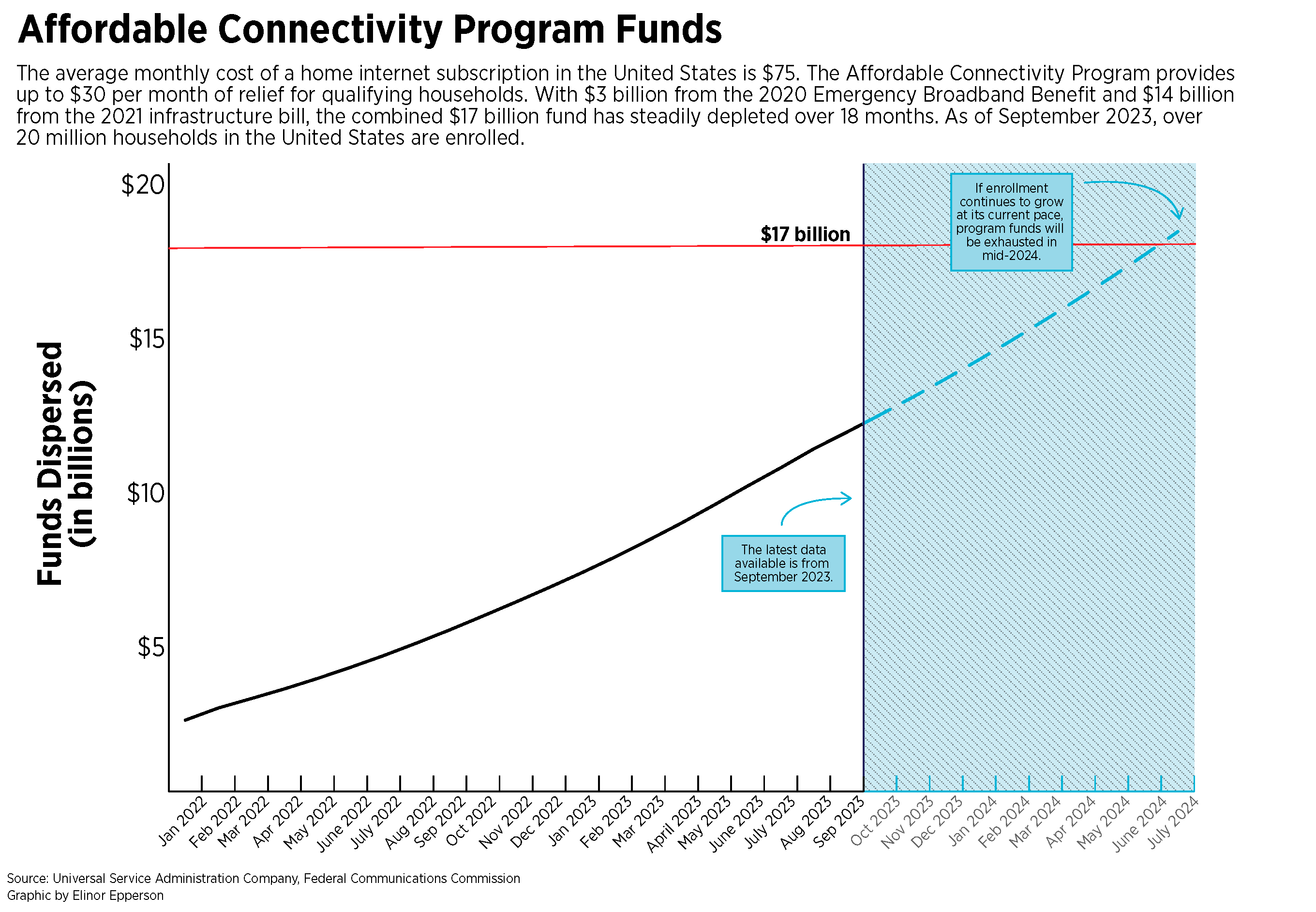

The Affordable Connectivity Program is a $17 billion portion of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021. The Federal Communications Commission oversees the program, which began dispersing funds in January 2022.

“It doesn’t solve everything,” Dagg said. “But [it] at least reduces the [monthly bill] quite drastically.”

Data from the Pew Research Center indicated that home internet use is significantly lower among U.S. adults that make less than $30,000 a year than their higher-earning counterparts. According to a study conducted by Consumer Reports, the average cost of internet (broadband or not) in the United States is about $75 a month — a potentially prohibitive bill for low-income families.

Merit’s survey of Ingham County found that 10% of respondents had canceled or reduced their service in the past year. About 75% of respondents without service at the time of the survey had internet in the past year. Dagg said this problem is “almost entirely an affordability issue.”

“That’s ‘this month, I can choose between having a cell phone and having Internet access,’” she said. “Or ‘I can choose between getting my tire replaced or staying online.’”

The federal program provides up to $30 per month for a single household’s internet bill. Qualifying households can also submit a one-time reimbursement request for up to $100 on a new device, defraying the cost. To qualify, households must fall below the 200% poverty level or receive federal benefits such as food stamps, housing assistance, veterans’ pensions, and/or Social Security Income.

But unlike funding for the Broadband Equity Access and Deployment Program, which the federal government allotted to states for distribution at the county level, the affordability program requires individual residents to connect directly with the federal government. To receive the discount, households need to first apply to the program online, then contact a participating provider and have the discount applied to their bill.

“It’s not necessarily the easiest thing to do,” Dagg said. “If you don’t have familiarity with it, or any digital skills, or even know what it is,” signing up for the program can be difficult.

Stephen said he had heard of the program but was unsure if he could sign up for it because he was already enrolled in Lifeline. This sister fund to the Affordable Connectivity Program helps low-income households pay for telephone service as well as broadband internet. FCC online resources say eligible households can enroll in both, but Stephen said he needs further clarification.

By the Numbers

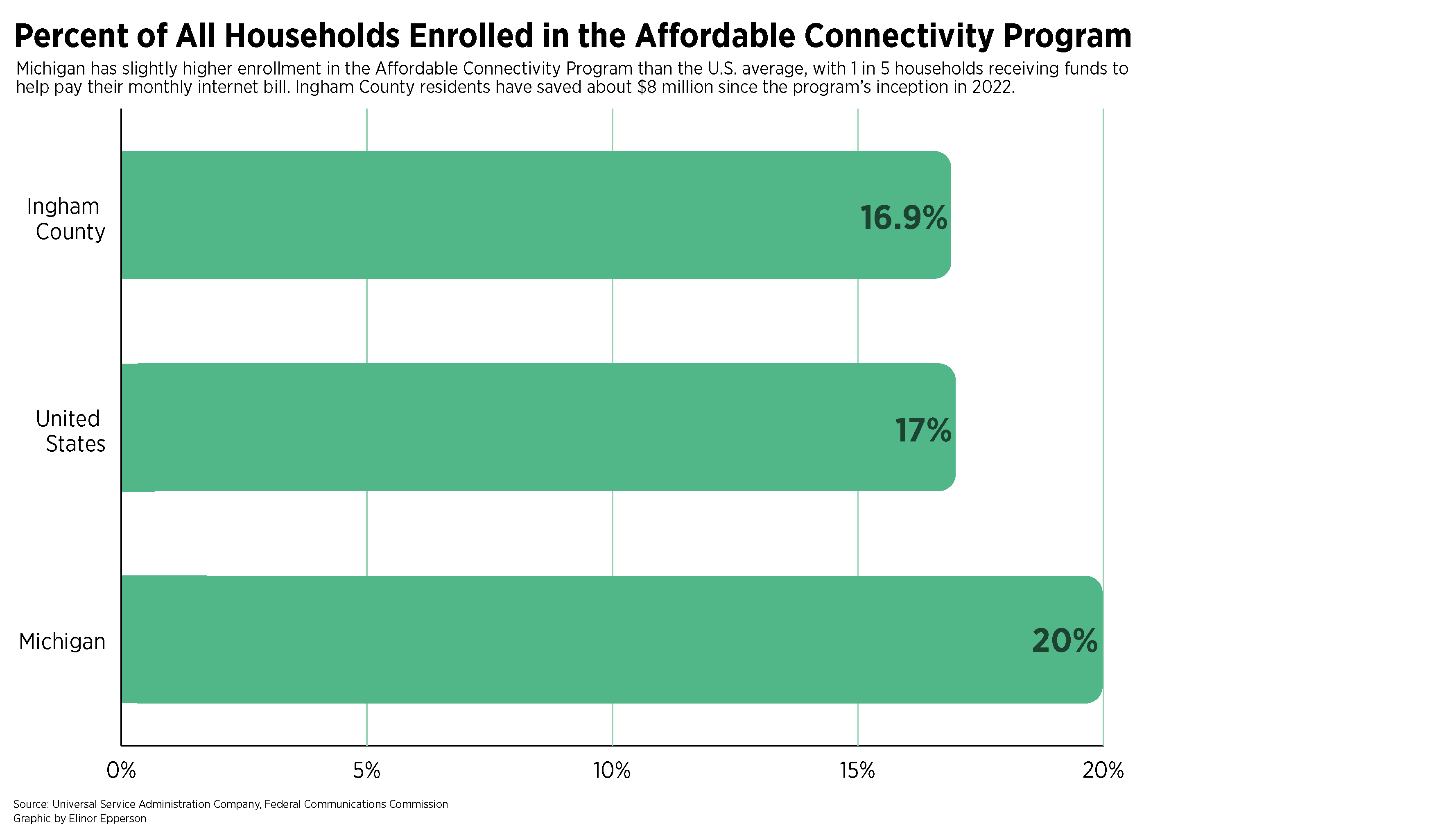

Enrollment in the program has steadily grown across the country to more than 20 million households. Michigan’s enrollment is higher than the U.S. average, with 1 in 5 households enrolled across the state.

Ingham County falls slightly below the national average, with 16.92% of all households enrolled. The program has saved Ingham County households approximately $8 million on their internet bills.

But with increased enrollment comes increased depletion of the fund. In early February, the FCC announced it was no longer accepting new applications and could run out of funds as soon as May.

An earlier projection by this author predicted that if enrollment continued to grow at the pace it had in the previous six months (about 3.27% per month), the program’s $17 billion could run out in June 2024.

Congress will need to act to replenish those funds, or millions of Americans could lose internet access at home.

Potential Solutions

Dagg said many communities across the U.S. use signup programs to help qualifying households access federal subsidies. Such a program would help residents like Stephen by bridging the gap between the federal government and individuals, giving them the information they need to receive as much aid as possible.

Knox said she has considered starting one at the library, but that it is outside the scope of their services right now. Instead, the Capital Area District Library could use an emerging strategy championed by digital equity advocates.

Digital navigators represent a holistic approach to addressing the digital divide, she said. Navigators are knowledgeable about local resources for internet access and work with individuals long-term to determine what they need to connect. They can be volunteers or paid employees stationed at community anchor institutions, like a library or school.

The Michigan High Speed Internet Office’s digital equity plan will rely on a statewide network of digital navigators, but that plan is still in draft status. Knox doesn’t expect any funds that could be used for such a program to reach the library until 2025 at the earliest. Neither Dagg nor Knox are aware of any Affordable Connectivity signup programs in Michigan.

Stephen emphasized that internet access is a necessity, not a luxury. “In order for people to have the freedom to have a real life, I think they really need to have internet access,” Stephen said. “There are so many things we all need, and most of them require the internet now.”

This is part of a series of posts from students at the Michigan State University Journalism School. The students will be covering four counties around Michigan during the 2024 campaign for the Detroit Free Press working with the American Communities Project typology.