After Two Years of Covid, Economic and Health Woes Persist in Diverse North Carolina Counties

The drive from Charlotte to Wadesboro, North Carolina, is not a long one. It’s a straight shot down U.S. Highway 74. But the road between the two cities — rolling by the Tesla dealership, past the strip malls full of fast-casual restaurants and into farmlands — tells a lot about how 50 miles can be the distance between different worlds.

On one end of the drive is Mecklenburg County, the most densely populated county in North Carolina, home to Bank of America and the NASCAR Hall of Fame. On the other is Anson County, where hogs outnumber people by a 2-to-1 margin.

In the last two years, everyone and every community in the United States have experienced the Covid-19 pandemic, but the ways they have experienced it and are positioned to emerge from it can look very different. And that’s true for places separated by just 50 miles of road, such as Mecklenburg and Anson counties.

Mecklenburg, a Big City in the American Communities Project’s typology, and Anson, a part of the African American South, show just how complicated the road out of Covid is. The pandemic presented different challenges and opportunities for both places that they are now just beginning to understand.

This winter, the ACP visited both counties to talk to leaders about how they and their neighbors have been weathering the pandemic and to understand what is next for them — economically, culturally, and socially. This report focuses on four factors in the two communities:

Economy and Opportunity

Housing and Development

The Pandemic's Impact on Health and Life

Voting Engagement

The hope is that by studying the differences in these two nearby communities, the ACP can shed some light on the nation’s complicated post-Covid landscape. (This piece is a companion to our newly released data report.)

Economy and Opportunity

Mecklenburg and Anson are a short drive from one another, but their economic structures, challenges, and opportunities are worlds apart.

Mecklenburg County

As a home to the biggest city in North Carolina, Mecklenburg County starts out with some advantages that provided economic insulation during the pandemic. When analysts talk about the knowledge economy of the 21st century, they have places such as Mecklenburg in mind. The county is a center for the banking industry and home to Bank of America, which offers the kinds of good-paying jobs that employees can do from home. The county is also home to the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, which has an enrollment of more than 30,000 and serves as a magnet for the young and educated.

The impacts of those different factors are evident in the Economic Innovation Group’s analysis of asset income at the county level (that’s income from dividends, interest, and collected rent). The per capita figure for Mecklenburg is more than $11,000. In nearby Anson County, the figure is about $4,600 per capita.

Those figures are enough to put Mecklenburg in the top 20% of counties nationally, while Anson sits in the bottom 10%.

The data before the pandemic and in January 2022 show that Mecklenburg has rebounded. The unemployment rate in January 2022 was very close to where it was two years previously. And, unlike much of the country, the community did not see a massive drop in its labor force. The figures for 2020 and 2022 are essentially unchanged.

But Charlotte is not without economic challenges coming out of Covid-19. Like many big, growing cities, its primary concern is creating an economic environment that works for its big, diverse population.

“I would say from an economic development perspective, one thing that we are challenged by here in Charlotte is this continuing evaluation of our upward mobility efforts falling short, you hear that all the time,” says Bobby Drakeford, founder of The Drakeford Company, specializing in residential development, urban housing, and land assembly brokerage. “The challenge I see there is so much economic prosperity and opportunity created by public investment that is not shared. … The resource rich are accessing public dollars more frequently than they used to, and there are not clear benefits to communities.”

Drakeford is talking about tax incentives that help builders and business owners expand and create jobs that tend to benefit the well-to-do in the county.

Mecklenburg sits just above the national the figure for economic inequity using the Gini Index — 0.486 versus 0.482 respectively.

There are, of course, some advantages in being surrounded by wealth. After all, the median household income in Mecklenburg, $72,300, is $5,000 above the national median. But as is the case with many Big City communities, spreading that money around is not easy. Mecklenburg is home to glass skyscrapers, upscale coffee shops, and expensive new condominiums, but that glittering downtown is a few blocks away from small single-story homes.

For all the bad of the pandemic, people working in the nonprofit sector in the county said it brought focus to long-standing inequities in the system — problems with good-paying jobs and affordable homes for those with degrees or jobs in banking, particularly the county’s African American community. The struggles of those with less were front and center, and the community rallied around the issues, at least for a time.

“It feels a little bit like our whole community was in a big room together. And there was a TV over in the corner playing this channel of what the needs are. And there was a blip where we had a big spike, but it's more like the volume just got turned up,” says AJ Calhoun, senior manager for data and evaluation at Leading on Opportunity, a nonprofit aimed at expanding opportunity in Mecklenburg. “But also people were like, this has been loud for a while, they kind of burned out on this. And so the mix of people that were watching the TV has changed a little bit. ... But fundamentally, I think we're back, kind of perhaps, where it was before.”

In sum, the community is emerging from the pandemic with a better of understanding of its needs. It still has the resources to try to address the challenges, but the pandemic’s eye-opening impact has faded.

Anson County

Anson County is different from its urban counterpart in most every way. The county is rooted manufacturing (advanced textiles and metal-working) and, to some extent, agriculture. Anson has not been attracting new residents. The county lost about 18% of its population between 2010 and 2020. And Anson’s median household income of $40,800 is only about 61% of the national median.

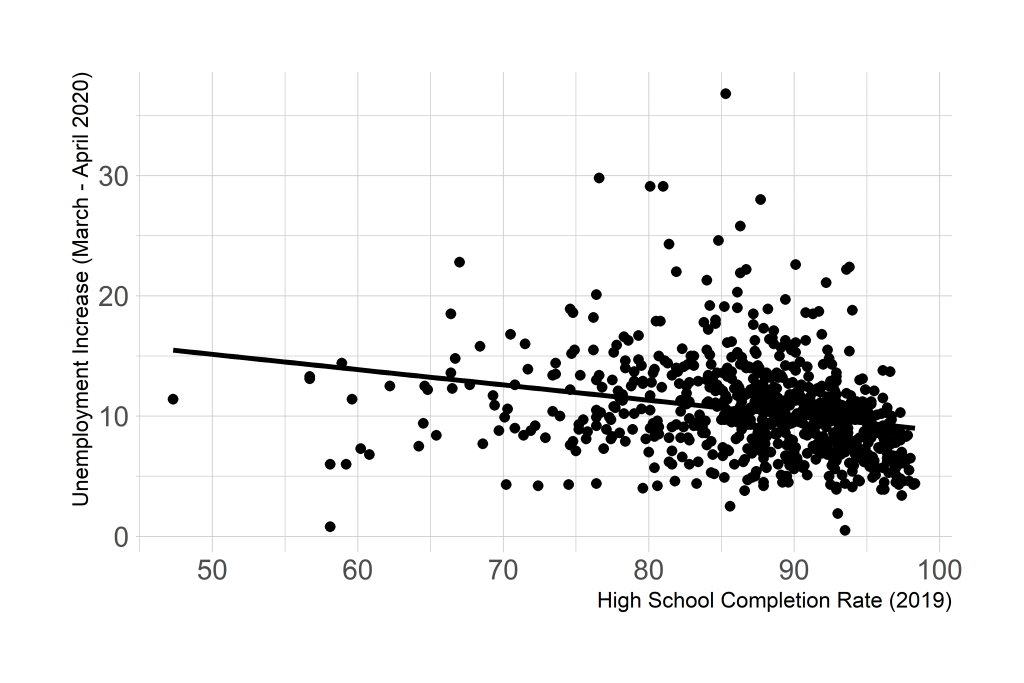

The roads here are marked by rural homes and poultry barns. A few small towns dot the landscape, including the county seat of Wadesboro, but drive through Anson and you will see a lot of open fields. While Mecklenburg is big and diverse, with good-sized Hispanic and Asian populations, Anson’s racial and ethnic diversity is primarily about white and Black residents — as is true for most communities in the African American South. Its 22,000 people are fairly evenly divided between African Americans and white, non-Hispanic residents. Only 11% of the population have a bachelor’s degree, and lower levels of education can be a challenge in the modern workplace.

“The hard skills that [employers] are looking for are math and measurement skills,” says John Marek, executive director of the Anson Economic Development Partnership. “The textile industry, they work with these very, very large pieces of machinery that are either milling machines, or weaving machines. And there's actually a surprising amount of math involved in setting up and running those machines. And folks just don't have the math measurement skills, and a higher-level ability to read instructions and understand them.”

Of course, those were all factors in the county’s economic story before the pandemic. And, as noted above, the county’s asset income figures reinforce the larger narrative of a community that lacks resources in key areas as it tries to emerge from Covid.

The employment story in Anson pre- and post-Covid is also revealing. In January 2020 before the pandemic took hold, Anson’s unemployment rate was 4.4%. In January 2022, the figure moved to 5.1% — and increase of 0.7 percentage points — but that doesn’t tell the whole story. Because along with that increase in unemployment, there was a decrease in the county’s labor force. Comparing January 2022 to January 2020 shows a decline of about 6% in the number of people working or seeking a job.

When adding to the unemployment rate people who have left the workforce, the figure climbs into the double-digits. That’s not to say that all of those people who left the labor force want to work again. Some may still be concerned about Covid-19, and others may have reassessed their lives and opted out of returning to work. But the drop-off is sizable and will affect the post-Covid recovery in Anson.

The future for Anson, however, may be serving as the bedroom of the growing population of Charlotte and Mecklenburg as the sprawl from the area moves eastward and touches the edge of the county in towns such as Peachland.

“You can get from town hall in Peachland to the Bank of America building in uptown Charlotte in 45 minutes,” Marek says. “That’s why those developments are being built … you're getting the hope that they will attract people who are commuting to Monroe and Matthews or Charlotte. And don't mind a little bit of extra drive for, you know, to save $20,000 to $30,000 on the cost of the home.”

The bigger question is what that movement means for Anson in the coming months and years. If the county evolves into an extended Charlotte suburb, housing prices will rise and the economy will likely transition to be more service-sector driven. While that could lead to an increase in employment opportunities, service jobs tend to pay less than those in the manufacturing sector. As housing prices rise in Anson, it could create economic tensions in the county.

The long-term plan for Anson, coming out of the pandemic, may be an investment and push to get high schoolers to continue on to the local community college, which is free for residents.

Housing and Development

Mecklenburg County

Money from banks, private equity, corporations, and investors flows into Charlotte for real estate development projects, including luxury apartments and homes — it can seem like cranes and construction sites are ubiquitous fixtures here. At the same time, Charlotte’s basement economic mobility ranking among large cities hangs over this city, based on the 2014 study by Harvard Professor of Public Economics Raj Chetty and his team. Chetty's subsequent report in 2020 notes the continuing obstacles Charlotte residents face in achieving the American Dream, in part because of neighborhood inequities.

Indeed, the city's wealth divides are felt deeply in housing, a sector receiving renewed attention during the Covid-19 crisis. The Charlotte Housing Justice Coalition, a grassroots volunteer organization, describes the city's housing problems as part of the legacy of Jim Crow and neighborhood segregation, particularly in the explicit displacement of African American neighborhoods during the urban renewal of the 1960s and ’70s. People were dispersed to insecure housing, living in what little public housing was built, never having a chance to purchase a home.

Over the years, Charlotte, a finance hub and historically very friendly to business development, has extended its welcome beyond the old boys’ network to investors around the world, the Charlotte Housing Justice Coalition notes. “There’s a lot of talk of equity and these historic tragedies, but when it comes down to it, it’s just business as usual,” says Ismaail Qaiyim, principal attorney at the Queen City Community Law Firm, who works with the Charlotte Housing Justice Coalition.

Making affordable housing more accessible is an uphill climb. North Carolina does not allow inclusionary zoning or rent control. The local government could leverage more of its regulatory power, Qaiyim says, and the Charlotte Housing Justice Coalition has helped organize neighborhoods and communities to compel local government to use this authority. The group can point to success in the recently passed 2040 Comprehensive Plan after organizing several historically distressed African American neighborhoods. “Working hand in hand with the Community Benefits Coalition, which is supposed to be the Congress of Neighborhoods, … that’s really going to be the thing that makes the difference at the end of the day, because it’s going to be all of the neighborhoods [coming] together,” Qaiyim says.

As a result of organizing and advocacy with the Community Benefits Coalition, two sections were added to the 2040 Plan. The first formally recognizes the Charlotte Community Benefits Coalition as a stakeholder. The second is a policy directive to develop community benefits strategy along with the Community Benefits Coalition. The 2040 Plan now also includes an Anti-Displacement Implementation Strategy and establishes two City Council advisory committees: the Charlotte Neighborhood Equity and Stabilization Committee and the Equitable Development Committee.

Mecklenburg County did take steps to handle immediate shelter needs when Covid-19 first hit the community in March 2020, according to WCNC Charlotte. As the outlet reported, Mecklenburg leased a hotel with 123 rooms for homeless people who tested positive or were suspected to have Covid, drawing on $300,000 in funds primarily from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to pay for the rooms, including security, rent, staffing, and cleaning. The county discontinued payment on December 31, 2021, when the funding ended. County leaders continued working to ensure shelters maintained quarantine protocols for positive cases. Another county program that funded hotel rooms for Tent City residents ended in September 2021.

In December 2021, the average rent in Charlotte was $1,472 for 942 square feet, according to Fox 46's analysis from RentCafe, with renters making up 41% of city households. Rents climbed more than 16% from 2020 to 2021. The biggest housing deficit is for residents who are at or below 30% area median income; more than 20,000 units are needed, according to the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute.

The housing problem is not abating. In early 2022, Bobby Drakeford said he’s involved in more deals than ever. He notes that 98% of the community’s affordable housing fund goes to rental properties, “which is not good economics for folks, since instead of building wealth and homeownership, they are tenants. The reason that happens is that it’s more expedient, I think, to talk about units delivered, as opposed to the impact of the units delivered. So, the rentals get you volume, but the substance is not what we need for economic mobility…. It’s easier to fund a rental developer than to help a bunch of homeowners.”

The Charlotte Mecklenburg Black Political Caucus, composed of more than 200 members in Mecklenburg County, has been trying to move the needle on this issue and recommended that 30% of the $50 million Housing Trust Fund allocation be devoted to homeownership initiatives.

Drakeford, a lifelong Charlotte resident, highlights the mindset challenges here. “I am not an affordable housing developer. I don’t do many public projects, but when I do, I always think about, you know, how equitable is it? And that’s just not how we are thinking here in every instance.”

But equity has different facets, he points out. “Real estate development in historically African American communities is a function of entrepreneurial capital…there are two sides to that equation. One is, you know, white folks are willing to invest but also Black folks have to invest. There is Black wealth in Charlotte. I don’t think much is coming into our communities. I live in the community I grew up in, not a particularly distressed community, but not a particularly affluent community either… I don’t think many of our corporate executives are investing in Black areas.”

In some ways, Drakeford’s background underscores how one’s childhood neighborhood makes a difference in one’s life path. His well-established neighborhood Northwood Estates was the only Black neighborhood in Charlotte’s history that had tennis courts and a swimming pool when he was growing up, although it’s experienced some decline more recently, he says. “A lot of folks I grew up with are involved in leadership positions in the city. And, of course, even growing up we had a lot of business owners in the community and professors and principals and doctors and lawyers as well. That’s not the case today. But most people I grew up with live fairly prosperous lives.”

Today, the housing gap continues to grow. Charlotte has been named among America’s 10 most overvalued cities, as homebuyers pay a 50% premium, according to a 2022 study by researchers at Florida Atlantic University and Florida International University.

Anson County

The problem of available and affordable housing isn’t confined to Big City’s Mecklenburg County. About 50 miles away from Charlotte in the African American South, Anson County Homes of Hope, based in the county seat of Wadesboro, provides housing to those in need through bridge, affordable, emergency, and rapid rehousing. The nonprofit’s mission is more urgent than ever. Says Executive Director Chipper Long, “The inventory is completely taken up. You can't really find a place to buy or to rent. We have just come out of the moratorium … people [who] did not pay their rent, they’re being evicted. And I’m getting sometimes five to six calls a day from people looking for shelter.”

You’ll find people sleeping anywhere they can find a space, Long says, in cars, in sheds, in abandoned buildings, under houses, under bridges, in the cemetery, and couch surfing.

To meet the great need, the nonprofit looks to take over property in low-risk areas, repurposing homes into apartments, like taking a three-story home on Park Road and turning it into three three-bedroom apartments beginning last June. The idea is for everyone to have their own space. In 2019, the nonprofit bought a duplex and renovated it, enabling two families to live there now.

Long eyes more projects. He’d like to be able to use public and private funds to renovate Anson County’s old textile mills for new housing. For example, he says, building a place for seniors of limited income could welcome those now forced to leave the county because they cannot afford the more expensive facilities available.

In recent years, Charlotte money has been flowing into Anson, skewing the housing landscape. Outside investors are buying and holding homes or fixing them up for rentals. “Anson County has become really hot because you can get more bang for your buck. The house that I live in would be over $1 million in Charlotte. And so, you’ve got land, you’ve got walkability, you’ve got community. That’s why they’re coming in,” Long says.

The Pandemic’s Impact on Health and Life

Very different populations, socioeconomic conditions, and densities have made for different pandemic experiences in the two counties.

Mecklenburg County

When the Covid pandemic hit in 2020, Mecklenburg had a few points working against it. Like other Big City counties, it is densely populated and, while it holds wealth and high incomes, it also holds neighborhoods with high poverty rates and poor housing stock. The county seemed like it was designed for easy spread of the virus — and holds populations likely to be vulnerable. But the case numbers largely followed the national trend. In fact, nearby Anson County had slightly higher overall case rates during the pandemic through late April 2022.

Nationally, the overall figure was about 24,500 per 100,000 people. In Mecklenburg, the figure was roughly 25,303 per 100,000 people. In Anson, the figure was about 26,700 per 100,000. Mecklenburg also had a lower Covid death rate than Anson, about 0.13% of its total population compared to 0.43% in Anson.

When people did get sick in Mecklenburg, hospital beds were available to care for them. The county has 2.2 hospital beds for every 1,000 people and 0.15 Intensive Care Unit beds for every 1,000 population. In Anson County, those figures are 0.6 beds for every 1,000 people and 0 ICU beds.

Hospital workers were stretched thin and pushed to the limit in Mecklenburg, of course, as they were everywhere, but residents had care in their community.

On the other end of the economic spectrum, Mecklenburg, with its high number of office and banking jobs, was in a better position to have a large portion of its population work from home. About 45% of Mecklenburg’s employees work in management, business, science, and arts occupations. That compares with about 39% nationally and about 25% in Anson County.

As a result, the skyscrapers that dominate the county’s skyline in Charlotte may have been dark for a time — Bank of America had 16,000 employees working from home during the worst of the pandemic — but the employees were still working in home offices and on kitchen tables.

Ultimately, the contours of Mecklenburg’s economy and the resources it had to apply to the pandemic may have shielded it from the worst of Covid-19’s impacts. The pandemic also brought attention to some of the community’s deeper challenges, however. The open question is whether the community uses this opportunity to address them.

Says Virginia Covill, deputy director of strategy and operations at Leading on Opportunity: “I think the hope is that in some ways, it feels like we're rebuilding a little bit, piece by piece, some of these things, and the layers are coming back on as things get busier. And so I think that is the hope as we look at everything from as simple as, ‘do I need to go into the office?’ … And I think that then translates to community work, too … ‘Are we putting all of the pieces back together in the right way?’”

Anson County

In the small, tight-knit community of Anson, the effects of Covid were felt more directly, changing the way friends and neighbors interacted. When you live a smaller community, the opportunities for interaction are often fewer and the loss of them can hit harder. Marek noted that Anson had an outbreak in its government center in late 2020 and virtually the entire government was infected; a couple of important people died.

There are a number of reasons why Anson had a harder experience with Covid than Mecklenburg. Its population is older and older people were more susceptible to the virus — more than 19% of the county’s population was 65 or older, versus 11.5% in Mecklenburg. And a far smaller share of Anson’s population has bachelor’s degrees compared to Mecklenburg, 11% versus 46%, respectively. That likely had an impact on how many people got vaccinated. Survey data show that those without college degrees were far more skeptical of the Covid vaccine than those with degrees. That’s reflected in the vaccine data in the two counties.

By the end of April, only 47% of the population in Anson had received two shots of the vaccine. In Mecklenburg, the figure was 64% — a 17-point difference. Survey data also showed African Americans were less likely to get vaccinated and roughly half of the population in Anson is Black versus about 33% in Mecklenburg.

But beyond the numbers, the biggest Covid impacts in Anson were more personal and struck at the fabric of the community, particularly around faith, says Rev. Alban Burney, pastor of the Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church, in Wadesboro.

“If there was a problem before Covid, Covid has exacerbated the problem. If attendance at church was spotty before Covid, Covid has now given people a reason to say hey, right, I don't think I'm coming back," Burney says. So that is what I'm dealing with, with my congregation, there's a little bit of depression, grief, about trying to get back to, to the way things once were.”

Religion matters more in Anson and African American South communities like it, compared with Mecklenburg and other Big Cities. Only 12% of the population in Anson is religiously unaffiliated, according to the 2020 Census of American Religion from the Public Religion Research Institute. In Mecklenburg, the figure is 24%. Those county figures largely match the numbers for their community types.

Burney says that during the worst parts of the pandemic, local ministers were torn over whether to open for services, particularly funeral services. They knew the gatherings would probably aid the community spiritually and culturally, but everyone understood the risks. At his church, as Covid waned, he still conducted Facebook Live services along with scaled down in-person services that had light attendance. It was necessary, he says, and the long-term impacts will be felt for a long time.

“Going to church was just part of their routine. On Sundays, it was a way to get out, it was a way to see people. If you've been around older folks, for a significant amount of time, you know that they are very set in their ways. And when something disrupts that it's tough. It is tough,” he said. “And so my role is to try to help them with that grief. But I also have to help them understand that church is not going to be what it once was; there are some people who will not be back,” Burney says.

In the audio clip below, Rev. Alban Burney describes the slow evolution of race relations and his own experiences in Anson County.

Voting Engagement

Covid-19 and unrest may have cast a long shadow over the 2020 election season, but North Carolina voters made their voices heard at the ballot box. Election officials in Anson and Mecklenburg counties ensured public health protocols were put in place to make things run safely and smoothly. Sherry Melton, Anson County’s interim director of elections, recalled masks being offered to anyone who needed one. Mecklenburg County Elections Director Michael Dickerson described giving voters a personal pen/stylus, so no one had to touch a screen; putting up sneeze guards; and providing staff with personal protective equipment. Community involvement was tremendous as Dickerson and his team scouted the county and grabbed up 33 early-voting sites, he said. The Charlotte Hornets and Carolina Panthers offered their stadiums free of charge — and gave voters free parking.

North Carolina has made voting easier in various ways, and many residents availed themselves of these means in 2020, according to interviews with elections officials in both counties. Melton remembers high traffic in the parking lot during early voting.

The Tar Heel State has a lot of experience with early voting, having adopted it in 2000. Its one-stop early voting law allows would-be voters to register and vote on the same day. They can choose to vote in-person or cast an absentee ballot in person during the two-and-a-half-week window. Or voters can vote absentee by mail. Once Election Day rolls around, registered voters must vote at their assigned polling place.

The state was one of just five with presidential, gubernatorial, and senatorial contests on the 2020 ballot. As in so many American communities, the 2020 presidential election was widely watched and fraught in these parts. Polling staff in Anson and Mecklenburg showed conscientiousness amid the scrutiny and increased interest, Dickerson and Melton said.

- In Anson County, overall voter turnout was 67% or 11,277 voters, and 63% cast ballots through one-stop early voting, while 7% mailed them absentee.

- In Mecklenburg County, the voter turnout was 72%. Of the 569,287 people who cast ballots, 65% chose one-stop early voting, and 24% opted to vote absentee by mail.

Overall turnout figures were six and five percentage points higher than in 2016. In November 2016, Anson County’s turnout was 61%; Mecklenburg’s was 67%.

In 2020, North Carolina’s presidential contest was so close that every county had to do a recount. It was an anxious time for elections officials. Melton and her staff fed all ballots through the machine again — a full day’s worth of work.

In a state colored red in presidential elections since 1980, except for 2008, both counties went blue in 2020, 2016, and 2012. In the past two elections, the counties’ different margins pattern the nation’s, i.e., rural locales gravitating more toward the Republican candidate and urban areas favoring the Democrat.

- In 2020, Anson’s percentage for Democrat Joe Biden was 52%; Republican Donald Trump received 48%. Whereas Biden got 67% of the vote in Mecklenburg and Trump garnered 32%.

- In 2016, 56% of Anson voters went for Democrat Hillary Clinton and 43% went for Trump. In Mecklenburg, Clinton garnered 62% of the vote and Trump received 33%.

Elections officials were under pressure after the November 2020 contests and, in Mecklenburg County, the tension seeped into 2021. Notwithstanding the national spotlight on people’s discontent — from the 2020 election, the ongoing pandemic, increased crime, school disruptions, and race relations — the 2021 municipal elections in both counties did not generate rousing turnouts. In November 2021, voter turnout was 13% in Anson and 15% in Mecklenburg. Whereas in November 2017, turnout was 12% in Anson and 21% in Mecklenburg.

North Carolina’s voting structures have been in flux of late, culminating in high-stakes court battles. In mid-September 2021, a panel of North Carolina judges blocked the state’s voter ID law requiring voters to show a photo ID, saying it discriminated against Black voters. The law was enacted in 2018 when the Republican-controlled state legislature overrode a veto by Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat. Republican leaders State Sen. Philip Berger and State Rep. Timothy Moore petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court in defense of the state’s voter ID law. On March 21, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in Berger v. North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP about who has the right to defend the law in court.

Redistricting was also roiling the state recently, bumping forward the primary election from March to May because the maps were being contested. As of seven weeks before the start of the rescheduled primary voting season, the maps became clear. On March 7, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed North Carolina’s congressional maps approved by the state court. The maps had been challenged by the Republican-controlled state legislature.

For the 2022 primary, featuring a competitive U.S. Senate race among other contests, early voting began April 28 and runs through May 14. Primary Election Day is Tuesday, May 17. Dickerson says he expects a robust turnout in Mecklenburg County.

Essential supplies had never been a part of our food pantry, but literally overnight, locating items like sanitizer, face coverings, and toilet paper became very important. Tracking these items down through our existing networks and reaching out to newly emerging networks were both time consuming and expensive. Food shortages began to hit our area and meat started to be rationed as prices sky-rocketed.

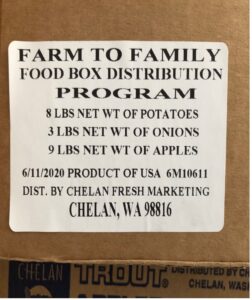

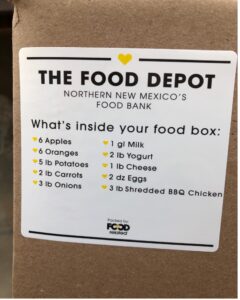

Essential supplies had never been a part of our food pantry, but literally overnight, locating items like sanitizer, face coverings, and toilet paper became very important. Tracking these items down through our existing networks and reaching out to newly emerging networks were both time consuming and expensive. Food shortages began to hit our area and meat started to be rationed as prices sky-rocketed. By June 2020 the food supply began to get back on track and most important to our pantry was the USDA Farm to Family program. Fresh produce had been really scarce all through March, April, and May until the fourth Wednesday in June. For the first time, we had boxes of fresh, healthy fruits and vegetables to give to every household. Later boxes sometimes had eggs, milk, bread, and other items. The pantry volunteers were excited to see pallets of these boxes delivered and so were the households that received a box or two, depending on the size of the family.

By June 2020 the food supply began to get back on track and most important to our pantry was the USDA Farm to Family program. Fresh produce had been really scarce all through March, April, and May until the fourth Wednesday in June. For the first time, we had boxes of fresh, healthy fruits and vegetables to give to every household. Later boxes sometimes had eggs, milk, bread, and other items. The pantry volunteers were excited to see pallets of these boxes delivered and so were the households that received a box or two, depending on the size of the family.

Edgar Oliveira, a resident of Mandan, North Dakota, owns a catering business in Mandan and a café at the state museum in Bismarck. He is also chairman of the board of the municipal parking authority and serves on the board of Morton County Social Services.

Edgar Oliveira, a resident of Mandan, North Dakota, owns a catering business in Mandan and a café at the state museum in Bismarck. He is also chairman of the board of the municipal parking authority and serves on the board of Morton County Social Services.

Becky Ofrane is Manager of Engagement and Partnerships for the City Health Dashboard housed at NYU School of Medicine’s Department of Population Health. Her work involves connecting with partners and city leaders to get data into the hands of those who can make a difference in health and equity.

Becky Ofrane is Manager of Engagement and Partnerships for the City Health Dashboard housed at NYU School of Medicine’s Department of Population Health. Her work involves connecting with partners and city leaders to get data into the hands of those who can make a difference in health and equity.  Holly Leber Simmons is the founder and principal of

Holly Leber Simmons is the founder and principal of