A Closer Look at Deaths of Despair in Montana

If someone wanted to design a place where the underlying causes of the nation’s Deaths of Despair epidemic were built into culture and geography, it might look a lot like Montana. The state’s staggering beauty contrasts sharply with the many challenges it faces around suicide, alcoholism and drug use.

In the U.S., people are more likely to die by their own hand in sparsely populated areas, and Montana has one of the lowest population densities of the 50 states. In a country where veterans, older men and gun-owning households are at higher risk, Montana has more of all three than the average American state. It treasures rugged individualism in a time when loneliness is commonly reported as a mental health problem. In a world where more suicides and attempted suicides occur at higher altitude, it sits on America’s Rocky Mountain spine. While it is well-known that effective treatment and follow-up for depression requires access to mental health professionals, Montana struggles to recruit and attract psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers. Montana has had one of the highest rates of suicide in the country for a century and bounces, depending on the years, between the top and slightly trailing positions in America’s rankings.

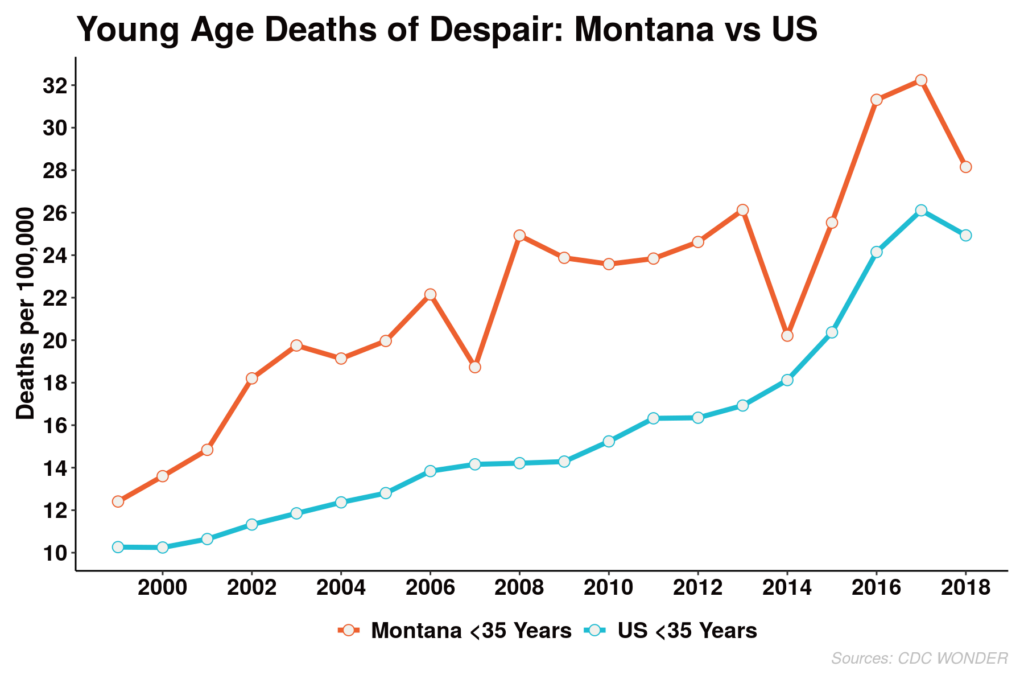

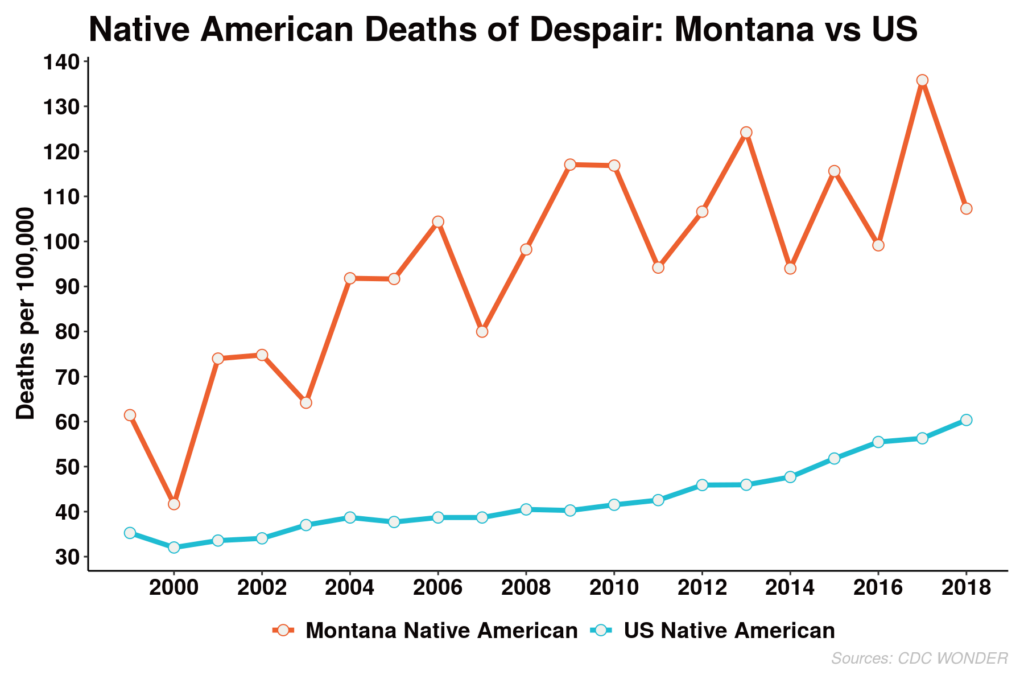

And so, as the United States saw a strong and steady upward trend in deaths linked to suicide, alcohol and drugs, Montana moved up in tandem with other states. History and geography, however, give the problems that lead to early death a particular, and particularly challenging, profile. Montana is seeing rising numbers of deaths among young people, and it’s seeing that trend among enrolled residents of the native tribes that call Montana home.

The Montana Landscape

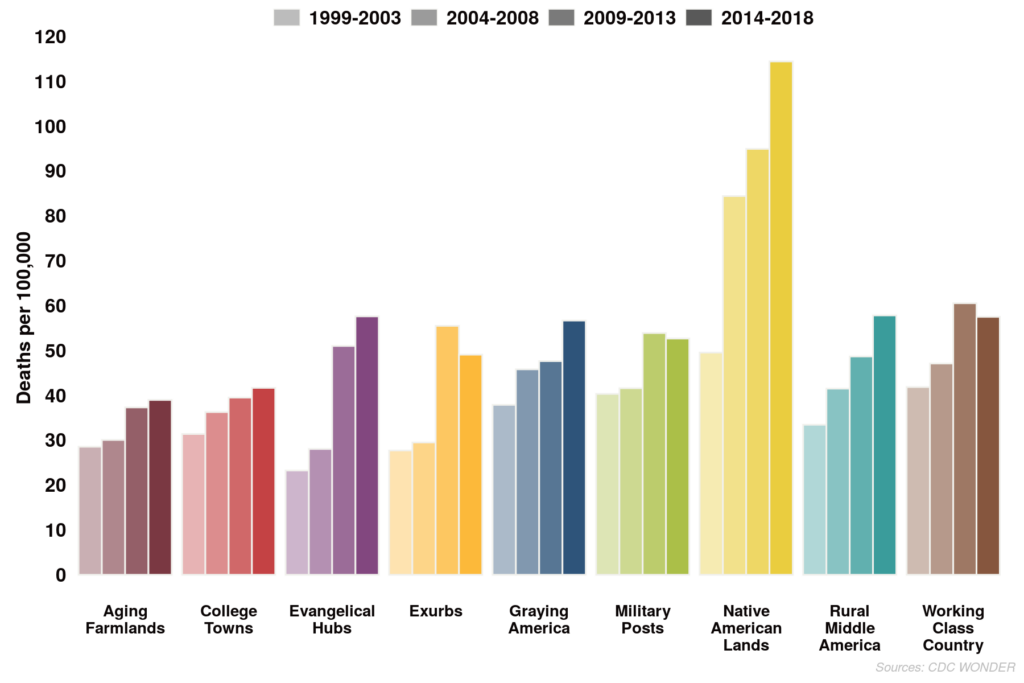

This piece is the second in a continuing series of reports on Deaths of Despair across the nation by the American Communities Project funded by the Arthur Blank Family Foundation. Our first report, in July, laid out the size and impact of the problem across our 15 county types. Data analysis and visualization are provided by the Center on Rural Innovation.

The state is not very diverse. The Census Bureau puts the white population at about 86% and the Native American population at roughly 7%, meaning Asian and Pacific Islander, Black, Latino, and mixed-race populations only make up about 4% of the state’s people. The trip from the western border with Idaho to the eastern border with North and South Dakota, at about 750 miles, is longer than the trip from Washington, D.C., to Chicago, which would take you through five or six states. And even if Montana is not known for racial diversity, it holds a wide range of different community types. Within those far-reaching borders are counties classified using the American Communities Project matrix as Aging Farmlands, Working Class Country, Rural Middle America, College Towns, Evangelical Hubs, Exurbs, and Military Posts. With just a few exceptions, these various community types have seen significant run-ups in the numbers of deaths from alcohol and drug abuse and suicide.

Clustered on the eastern end of the state, the Aging Farmlands have seen a gradual rise in the deaths of despair. And on the western border, the counties that make up Montana’s Working Class Country have seen significant rises in all classes of early deaths.

Deaths of Despair by Year Groups [Colored by ACP Types]

A Long List of Challenges

I meet the state’s suicide prevention coordinator, Karl Rosston, as he is about to begin a training program for nurses on warning signs for people contemplating ending their own lives. “We’ve been in the top five for the last 40 years. As a matter of fact, we’ve been near the top since we started keeping data in 1918.”

At a cafeteria table at Montana State University in Bozeman, he describes a daunting set of variables, some of which have a solution, many of which don’t. “We’re a northern state. We have vitamin D deficiencies because we have less sunshine. And Vitamin D deficiencies are correlated with higher risk for depression.”

The opioid overdose problem that has been ending tens of thousands of lives in America for years is present in Montana, but not a leading factor in early death. Rosston noted that in 42% of his state’s suicides, alcohol was found in the body, the rates for opioids and other drugs are much lower. “I see a lot of people who use alcohol to self-medicate their depression or anxiety. There’s one problem with that, alcohol is a depressant. Using a depressant to medicate your depression is not going to work too well.

“We’re near the top in the nation in alcohol consumption per capita, in alcohol-related deaths and DUI. And then you throw in access to lethal means,” which, in Montana means firearms that are easy to acquire in the state, “and you have a really major issue. Because bottom line: Nationally between 70 and 90% of suicide attempts are by overdose, but it’s one of the least lethal means, anywhere between 3 and 11%. But when you use a firearm it’s more like 90%. Nationally about 51% of all suicides are by firearm, in Montana it’s about 63%.”

Isolation is a problem. Simply put, at 147,000 square miles, but just a little more than 1 million people, much of the state is empty, or close to it, at a population density of just 6.7 people per square mile. It has about the same population as Rhode Island in an area about 95 times the size. Isolation is bad for depression, and vast distances make for practical challenges, said Rosston. “At the law enforcement academy, they tell me it can take an hour and a half to two hours to respond to a 911 call.”

When I asked Rosston, who reviews the death certificate of every suicide in the state, to give me a recent, typical case, he said, “You have a 40-year-old male, who has had a recent divorce. May have quit his job or is not working, chronic pain. Uses a firearm. Recent history of increased drinking. That’s the profile I see all the time. The relationship component is huge, as is the firearm.”

However, the disturbing growth Rosston sees in the numbers are not among the middle-aged white men, the military veterans or the chronic pain sufferers who have long buttressed Montana’s deaths of despair figures. Rather, he sees worrying signs among young people, and especially Native Americans, both in urban areas and on tribal lands.

Every state in the union contributes data to the national Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Montana’s 2019 numbers are sobering reading for anyone trying to understand the rise in deaths of despair. More than a third of the state’s teens say they felt so sad or hopeless for two weeks or more in a row during the previous year they stopped going to school. More than a quarter thought about suicide, and for about one out of five, it was serious enough to contemplate a plan for ending their lives. One in 10 had actually attempted to end their life. In contemplating, planning and attempting suicide, the rates for girls exceeded that for boys. Almost a quarter of high school girls, 23.5%, reported making a plan to end their lives, a rate roughly twice as high as that for high school boys at 12%. Some 12% of girls reported they had attempted suicide, a rate about 50% higher than that reported by high school boys. For boys and girls, the rates of all these suicide-related behaviors exceeded the national average. Among their Native American peers, the attempted suicide rate was almost twice as high.

The numbers are no surprise to Christina Powell, co-director of Bozeman Help Center, a crisis hotline. “If there’s a common thread, it’s the ability to tolerate loss. And when I say loss, I’m talking about everything. From things like, you know, a girlfriend or a boyfriend. Loss can be everything: loss of job, loss of status, relationships, loss of family. Loss is in some ways perceptual, in many ways concrete. All human beings experience a level of loss throughout a lifetime. That’s to be expected. Loss seems to be consistently there in moments of despair.”

THE CRISES FACING NATIVE AMERICAN YOUTH

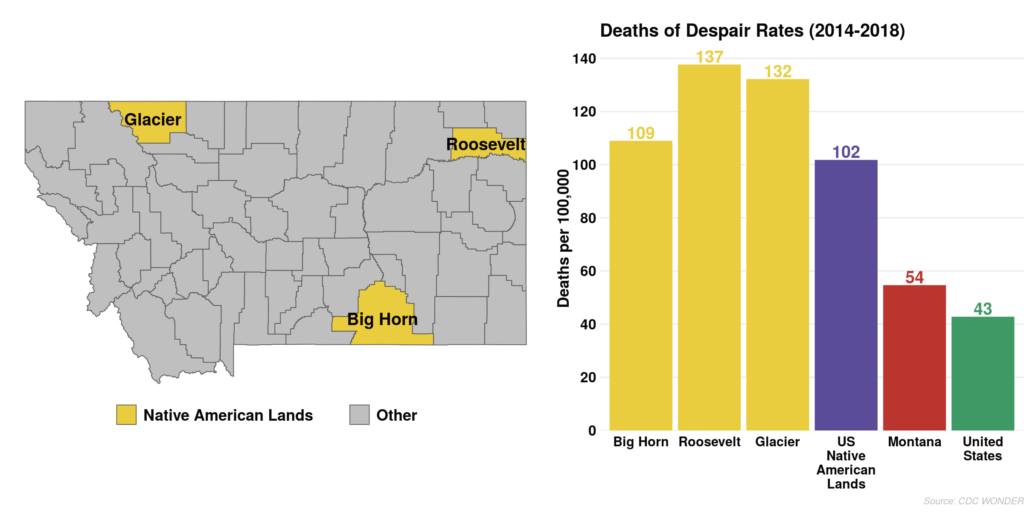

The Deaths of Despair numbers are particularly concerning in the Native American Lands county type in the ACP. Our first report noted how the rate in the Native American Lands of 101.6 per 100,000 people, was nearly three times the national rate of 38.3. And several Native American Lands counties in Montana (Big Horn, Roosevelt and Glacier) sit above the national figure for Native American counties. The roots of those high numbers are deeply tied to larger historical and cultural challenges in the Native American Lands counties.

Educator, activist and Crow tribal member Shane Doyle sees despair on the reservations, and says it makes sense, given what teenagers are up against. The Crow Reservation is mostly in Big Horn County. “Look at what has occurred here over the last 150 years. If you’re a kid, you think it’s normal to live in utter poverty. You think it’s normal to face a cascade of health issues. Unless you can see your way through to the issues of how we got here, you’re going to be weighed down by fatalism.

“If you can’t describe how Native people were once proud and strong and healthy and resilient, if you can’t conjure that up in your mind, it’s going to lead you to believe either Native people deserve this, or are stupid, or lazy. Or you believe the myths, we can’t handle alcohol, or how you don’t fit into society. Myths made popular by books and media and movies.

“If you decide you don’t want to accept it, what options do you have?”

Speaking to tribal members and other Montanans, on the reservations and off, a phrase kept popping up in interviews: “historical trauma.” It can’t be measured by researchers, it can’t be tracked from year to year, or compared in state-by-state tables. For adults trying to head off the suffering and early death so common in Indian families, that trauma is as real and tangible as statistics about high school completion or drug possession.

“Think about what it’s meant to experience generations of catastrophic and cataclysmic loss,” Doyle said. “The whole process started with smallpox, diphtheria, typhoid, diseases brought here from outside. That was just the beginning of hard times for Native people here. Most of them lost at least 75% of their communities, then land stripped away.”

Along with poverty and physical suffering came cultural eradication, with children moved off tribal lands and away from families to boarding schools, not once, but for generations of children, an intentional stripping away of ancient languages and cultural knowledge. Doyle said, “It’s a community that’s been traumatized for well over 150 years, and hasn’t been able to regain its independence.”

The land is stunning. Jagged mountains emerge from golden grasslands. Threads of cloud crisscross the renowned sky. Suddenly curious cows raise their heads in unison to watch a single car come by on a gravel road. All that breathtaking beauty can’t hide the worn mobile homes, the sparse store shelves, the cracked windows mended with masking tape to hold the powerful wind rippling the roadside brush.

Confronting the Problems

Alma Knows His Gun McCormick is the executive director of Messengers for Health, a program on the Crow Reservation bringing education, advocacy and health services to tribal members. While identifying the need for better healthcare on the reservation as an important issue in fighting deaths of despair, McCormick does assign a role to historical trauma, as well. The role of rejection in the history of her Crow people and other Montana tribes is underestimated, and it binds her people to this day. “We see the natural events, boarding school, broken treaties, racism,” she said. We can describe those facts, but underlying all of it, it’s a spiritual thing … it’s rejection. Because of being displaced, having our lands taken away, assimilating to a culture different from ours, we experience a spiritual rejection.”

McCormick connects her people to essential health services and the latest diagnostic procedures, and at the same time assesses something harder to see, “a heaviness” that keeps her people in its strong grip. “That identity, those values, that’s what has kept us over the years, facing adversities of historical trauma. That is how we have overcome.”

McCormick said the Indian Health Service, an arm of the federal government, makes mental health treatment available for tribal members, but stigma makes even those in deep trouble shy away. “They don’t seek it out. Confidentiality is key and, unfortunately, that’s one of the barriers that keeps people from going to Indian Health Services, lack of confidentiality. And not only in the area of mental health, just going and receiving healthcare.”

In small communities like Crow Agency, it is well-understood that people have mental health and drug counseling needs, McCormick said, but there is little confidence that a family’s private matters would stay private. “Information seems to leak out. Everyone knows everyone. If they went to an appointment, maybe they were diagnosed with something, or if some things going on, information goes out.”

If they try to go elsewhere, it can mean a long drive. “People have to go into Billings if they want to see a specialist. It’s a hundred miles round trip, and transportation can be a significant barrier to people seeking healthcare.” During the COVID emergency, burning through Montana through the autumn and into the winter, McCormick was able to use pandemic relief funds from the state to issue $30 gas cards, which allows a reservation family to make the long trip to the state’s biggest city. Some communities on reservation land are much farther away, and get a $40 card to cover the gas.

As a licensed clinical social worker, and a man immersed in data from his state and around the country, Karl Rosston easily rattles off the numbers that define his state’s challenges from untreated pain to distance to the nearest psychiatrist.

He also cites both historical trauma and an alienation from the tribal past as big factors in suicide rates on the reservations, about twice the national average. “Where we often see a huge gap is between the youth of the tribes and the elders. The elders, one of their main jobs, is to pass down the traditions of the tribe. We see a huge gap where these kids are not learning their culture, not learning their language, not learning their healing ceremonies, and you have a generation of lost kids. Then they’re exposed to poverty and addiction and crime and gambling and everything else evident on our reservations, and you can understand why you have such a high rate of despair, and suicide.”

Underlying Issues

The pain of too-early death is present across the Native American Lands counties of Montana. There is a strong desire for change, and there’s an acknowledgement that high levels of family dissolution, substance abuse and joblessness cannot be changed overnight. Lack of daylight and altitude that reduces the effectiveness of anti-depressants are impossible to change. Tribal members wrestle with the long- and short-term nature of their challenges and try to find near-term solutions that save lives, while still wishing to tackle the big, structural problems.

Peggy White Well Known Buffalo said she saw problems everywhere she looked on Crow lands: drug abuse, alcoholism, domestic violence and threats to the maintenance of the language and the tribe’s traditions. With her Center Pole project, she tried to pick off those problems one by one, providing a cultural hub, a source of nourishing food, and training in Crow arts and traditions. We talked in the Center Pole’s café as she gave instructions and greetings in Crow to workers and volunteers bustling in and out.

White said a vision during a traditional sun dance pointed the way. In her vision, she walked past tables full of food and saw an Indian man who told her to “feed the ones that need it. Give it to people who don’t have.” Switching back and forth between English and Crow in the story, she recalled, “I know what it is not to have food. I can remember not having enough to eat.”

Reluctant to use the term “mental illness,” White recalled her own grandson’s death, just weeks before. In a video addressing White, her grandson apologized for ending his life and forced her to look back in regret, and wonder why she had not done more to pull the young man into her orbit. “Why didn’t I check on him when I didn’t see him for six months. Why didn’t I try to guide him in my spiritual beliefs? Why didn’t I try to spend more time with him? It was really hard.”

White works with recovering alcoholics and drug users, as well as children and adults who have suffered domestic abuse. Lightening the burden of historical trauma, White said, requires an approach to Native people that preserves the best of their past to bring healing and balance to the present. She takes young people to Crow holy places, teaches them the use of native plants for religious customs and herbal remedies for medicine.

Young Tribal Members

McCormick is committed to getting her people treatment, and she wants to find an approach that incorporates a heavy influence of Crow traditional teaching into a community health model to combat substance abuse and early death. “We are designing it right now. We’re researching intervention on how to improve self-care when people have chronic illness. It shows very strongly our people need mental and emotional wellness support. We set up a support group with our cultural ways, our language, our kinship, our wisdom passed down.”

Collena Brown grew up in the tiny town of Grass Lodge and has lived there almost her entire life. She watched as the local Boys and Girls Club, run by the tribe, lost its charter and went belly-up. Though her family was preparing to leave town for new work, Brown instead revived the charter, and is running her new club separately from the tribal administration. “We started everything from the ground up, from finding board members, finding funding. I had never written grant applications in my entire life.”

The new Boys and Girls club was finding its feet just as the Crow reservation grappled with the coronavirus pandemic, and school-age children were sent home to learn remotely, with very little support or follow-up for remote, self-guided learning. Toward the end of the year the schools remained closed. Brown is trying to keep kids current with their studies while supporting parents who must work. “The kids know that we’re there, that we’re here to help them.” The Boys and Girls Club is hiring high schoolers as tutors, and raising up leaders at the same time. “We’re teaching them the joys of having a job. The responsibility of looking after themselves. We don’t take calls from parents. If you can’t make your scheduled shift, you have to call.

“We’re making sure the teenagers know what responsibilities they have.”

She worries about the threat of early death, the kids she can’t reach in time, and what to do about their memories. “We almost glorify the ones who had committed suicide. We have to remember them, but I don’t think we should make it bigger than it is, so that the youth see it in a good light.”

Brown said she sees teenagers who are nearly on their own, with loose association to broken families, and homes far removed from other connections. “They have no relationship with their parents. No support whatsoever. A kid is looking for a safe place, somebody who will listen to them. In town, it’s a little different, maybe you have to be a little careful where you go. But farther out? A lot of them are stuck out there.”

Overcoming Isolation and Finding Meaning

That isolation, that lack of connection, is dangerous for people in crisis whether they find themselves miles from the nearest town on the Crow lands, on a farm first planted by European ancestors at the turn of the last century, or in one of Montana’s small cities. Kathy Allen trains the crisis counselors who work the phones at the Bozeman Health Center, and said the combination of shame and isolation leads people to crises they conclude they cannot share with the people around them. So they end up on the phone. “Part of our job is to reduce that shame, validate that the person is in pain, that of course these thoughts are coming up for them.

“I talk to a lot of teenagers who feel shame about reaching out. In Montana, there’s a mentality around not needing help, being able to get through things on your own.”

Resilience, and the lack of it, was identified as a culprit on reservations and off, among people of all races and ages. “It’s not just money,” said Shane Doyle. “You can’t just give a kid money and say, ‘Now go and be happy.’ There are a lot of angry young men here in Montana. And they’re angry because they haven’t been able to connect and express their humanity.”

Karl Rosston wants to screen for depression among every child in the state by the age of 15, a common age of onset, to get help early to someone who might otherwise endure decades of suffering that ends in early death. He is training nurses around the state to look for the behavioral clues to someone more likely to die a death of despair. “The more tools they have, the better they’re going to be able to recognize and identify these people that are at risk.”

Christina Powell wonders about what has changed in society. She knows there are a lot of walking wounded among us, and at the same time wonders if it is the challenge of daily life that has changed, or us? “What is our ability to tolerate loss? Is it being degraded as time goes by? Is there an increase in the experience of loss? That’s hard for me to believe.

“Are we adequately preparing our children to face loss?”

Shane Doyle said we never ask the most obvious question: “What does it mean to have a high quality of life? Our education system has been built to produce workers.

“How about happy human beings?”

Ray Suarez is co-host of the public radio program and podcast World Affairs, and covers Washington for Euronews. He is the author of three books on American life, most recently Latino Americans: The 500-Year Legacy That Shaped a Nation.