How Montana’s Despair Deaths Have Intersected with the Pandemic’s Isolation

There have been a lot of anecdotal accounts of suicide and overdose rates surging during the pandemic. From early reports from Colorado about a tripling of the drug overdose rate to reports from Nevada about teen suicides as young people struggle isolated from schools and peers, the stories are compelling, but incomplete.

The American Communities Project worked with the Office of Vital Records at Montana’s Department of Public Health and Human Services to get a statistical understanding of the tumultuous intersection of Covid-19 and deaths of despair. The state allowed the ACP to analyze 197,000 death reports from 2000 through the end of 2020 to identify trends and see what may have happened during the worst of the lockdowns and social isolation.

Overall Findings Reveal Alcohol’s Effect

After examining this statewide data over the 20-year span, 2020 stands out in a few important ways:

-

- First, the surge in alcohol-related deaths was significant both in terms of the rate and the actual number of deaths.

- Secondly, the suicide rate remained largely flat despite the pandemic’s forced isolation and the interruption to normal routines.

- Drug overdoses appeared to be on the rise, but that is mainly attributable to a spike in April. Since then, the numbers have declined steeply.

Despair Deaths Through the ACP Lens Show Volatility

When one examines the same reports through the lens of the American Communities Project, the story of what happened to communities during Covid becomes much less consistent.

As the ACP reported in late March, initial comparison of deaths from Covid and deaths of despair find the mortality rates vary depending on economic and cultural factors.

The same holds true in Montana, but with a sparse population and large counties, data from Montana are often more volatile as individual cases can swing numbers in a county.

But still, sorted through the ACP community types, the portrait of Montana’s fight against deaths of despair during Covid becomes very different.

While deaths of despair appeared to drop toward the end of the year, 2020 still was a record bad year in three different community types in Montana: Native American Lands, Graying America, and Working Class Country. In each of these community types, the deaths of despair rate was up significantly from a five-year average.

Spread throughout the south-central part of the state and along the Rocky Mountain Front, Graying America comprises counties with older populations. Working Class counties are situated in the northwest corner of the state. These two community types saw their deaths of despair soar due to suicide increases. In particular, the three Working Class counties of Lincoln, Sanders, and Mineral saw steep jumps in the number of suicides in 2020.

Although the news was also troubling in Native American counties like Big Horn, Glacier, and Rosebud, where the deaths of despair rates climbed due to major jumps in alcohol-related deaths.

The sparsely populated Aging Farmland counties and College Town communities like Missoula and Bozeman saw either drops or little change during the pandemic.

But even amid these numbers there were promising developments.

Perhaps most striking is the drop in drug overdoses in the state. Overdose rates dropped across all community types, with the steepest drops in rural and Native communities.

Those same communities reported significant declines in suicide rates, as well, with Native counties seeing the largest — a jaw-dropping 49% drop from the five-year average.

It is too early to tell if these mixed experiences during the pandemic will play out similarly nationwide, but in Montana, drug overdoses seemed to drop as the travel limits and lockdowns dragged on and many communities saw a drop in suicide, although there are some troubling exceptions to that trend.

A safety net tested

If there is positive news in the deaths of despair data during the pandemic, it was in the general drop in drug overdoses throughout the state and a targeted drop in suicide rates in large swaths of the rural parts of Montana.

The reasons behind these numbers are more hypotheses than direct evidence but experts point to important changes in healthcare and government policies that greatly improved access throughout rural Montana.

In 2015, the Republican legislature working with a Democratic governor hammered out a deal to expand Medicaid in the state. The program, which was renewed in 2019, offered coverage to at-times nearly 100,000 people in a state with a population just over a million.

For providers in rural and low-income communities this program stabilized care and kept small hospitals and clinics open.

One federally authorized clinic that offers care in Bozeman and more rural communities around it said that before the expansion 56-58% of patients they served were uninsured. That number is now 9-10%.

At the state’s largest healthcare policy nonprofit, Dr. Aaron Wernham said the system kicked in in two important ways in 2020. Ahead of the pandemic, Medicaid expansion enrollment had dwindled to about 80,000.

But then Covid hit.

“When the pandemic hit and people lost their jobs, the program functioned as it’s intended to, which is as a safety net,” Dr. Wernham said. “When something goes wrong in your life, so if you lose your job, you all of a sudden have no income. You’ve lost maybe employer-sponsored insurance. Medicaid picked up the pieces, so we have seen enrollment in the program go back up into the low to mid 90,000 range.”

In addition to the program being there for those with low incomes and for the nearly 17% of Montanans who applied for unemployment during the pandemic, the program also kept the lights on at hospitals.

“Every emergency room in the state, basically any nonprofit hospital, which accounts for almost all of our hospitals, is obligated to see everybody that walks in the door,” he said. “You know [the program] really helped keep hospitals afloat… You can’t check their insurance before you decide if you’re going to take care of their Covid.”

An unlikely hero: the government

With Medicaid offering emergency insurance for those buffeted by the pandemic and reliable payments to hospitals and clinics, the system could stay open, but healthcare providers who were seeing patients also realized that they needed to try to move as much care as possible to telehealth.

“When you talked about rural health everyone was like, ‘well, gosh, telehealth, that’s what you should do. Why are we not doing this’ and it just never took off,” said Scott Malloy, program director at the Montana Healthcare Foundation.

Both the foundation and care providers like Lander Cooney at the Bozeman-based Community Health Partnership clinic said for telehealth to be effective key rules had to change.

Then came what Cooney called “an incredible two weeks in March.”

The federal government made three emergency decisions that changed the face of telehealth, especially in rural states like Montana. First, government insurance programs said they would pay the same amount for telehealth visits as they would for in-person treatment.

But just as important, the government said they would allow patients to receive telehealth treatments in their home and the provider could also be in their home.

That is, before March 2020, telehealth was only covered if the patient came to a clinic. Then they could see a doctor who was in another clinic.

When the laws changed, state governments like Montana worked to quickly draft emergency rules to allow telehealth to move online.

Cooney noted that moving behavioral health to video conferencing or the telephone did two things, it enabled them to offer uninterrupted services to patients and allowed clinics to use the freed up office space to create a safer location for in-person medical care.

She said within a month, nearly 90% of all behavioral health visits were fully online or by phone. The comparison is striking. In 2019, Cooney’s clinics conducts about 100 visits for both medical and mental health visits. By the end of 2020 that number had jumped to more than 15,000.

The clinics are moving toward a return to in-person treatment that never fully went away, but for Community Health Partners, Cooney said, some things have changed.

“Like any business, we need to say, ‘Let’s not go back to the old ways of doing things just because we can. Let’s consider what has changed in the past year,” she said, adding part of that would be to find the “ideal applications of telehealth.”

Screening via screens

This shift to telehealth was happening at a time when the state has also been expanding what the Montana Healthcare Foundation calls behavioral health screening.

Dr. Wernham pointed to the fact that years ago screening blood pressure was not the norm and that lack of screening prompted a “catastrophe” in terms of cardiovascular disease and death.

“We think of drug use and alcohol as being the same thing. You can’t look at someone to know if they’re depressed. You can’t look at someone and know if they are suicidal. You can’t look at someone to know if they’re addicted,” Dr. Wernham said, adding, “so you need to screen for those things just the way we screen for blood pressure, and if you’re not doing that, you know you’re at risk of missing a lethal condition.”

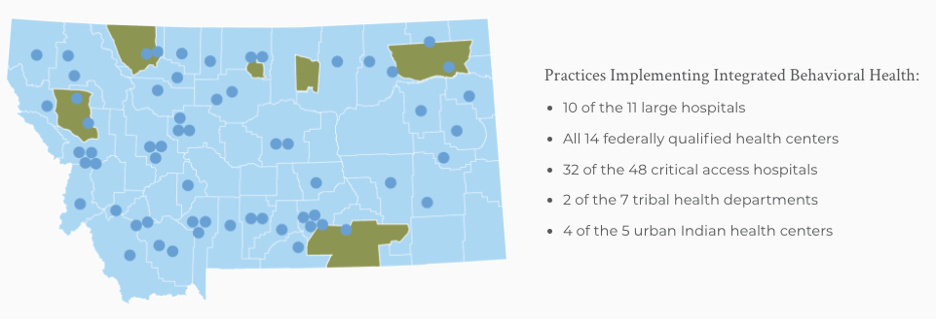

Most of those clinics and hospitals accepting Medicaid and other insurance have expanded the use of behavioral screening to identify drug and alcohol issues as well as depression. The concept, called integrated behavioral health, adds these checks to normal medical visits, not just those seeking some type of mental health assistance.

“By expanding telehealth access, we were more able to reach people in crisis in rural areas, at the same time as having more practices in rural areas now engaged in screening everybody that comes in, through their doors … for depression,” Dr. Wernham said.

This combination of integrated behavioral screening and telehealth is not the sole reason for drops in drug overdoses or suicide rates going down in rural places, but they have clearly helped communities in Montana weather the pandemic. It’s important to note that these changes rely on emergency declarations from federal and state governments.

As the pandemic eases, questions remain about pay parity and telehealth. Communities in far-flung Montana may be deeply affected by the result of these conversations and the continued availability of safety nets like Medicaid when it comes up for renewal in 2025.

Associate Professor Lee Banville joined the University of Montana faculty in 2009 after 13 years at PBS NewsHour, where he was editor-in-chief of the Online NewsHour.

Associate Professor Lee Banville joined the University of Montana faculty in 2009 after 13 years at PBS NewsHour, where he was editor-in-chief of the Online NewsHour.