In a New Mexico Mountain Village, A Tale of Two Carrots

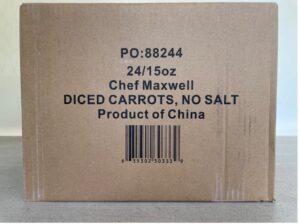

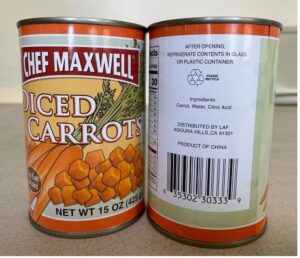

The other day while pulling tasty carrots out of the ground in my garden, each emerging with the aroma of the sweet earth clinging to its rootlets, I couldn’t stop thinking about the food pantry carrots. Several months ago, one of the volunteers at the Ojo Sarco Community Center Food Pantry asked if I knew the canned fruits and vegetables stored in the pantry were labeled as products of China. I am the shopper for the pantry and this information was very distressing.

Ojo Sarco, New Mexico (in Rio Arriba County, a Hispanic Center), is an isolated mountain village of 300 or so people located about two-hours round trip to full-service grocery stores and most other services. This narrative is a microcosmic view of how one small community responded to the pandemic and was a role model to other communities. Over the past 18 months we have learned hard lessons about the global food system and the curse of the supply chain. We have also become aware of the policy changes needed to provide healthy food for people, no matter where they live.

Meeting Greater Demand

When the pandemic began in March 2020, the community center was very quick to implement covid-safe public health precautions. It was so early that initially there was some pushback to the precautions. But, because I have a Master in Public Health degree with specialization in occupational and environmental health, I urged the board and community to support strict safety guidelines. As it turned out, similar practices were later mandated by state and local government and voluntarily adopted by other organizations.

Immediately after the first Safer-at-Home order was issued in March 2020 by Governor Lujan-Grisham, pantry deliveries were doubled from once a month to twice a month. The number of participating households increased. Our public outreach emphasized that receiving food and essential supplies in the village and reducing the numbers of trips to town was a public health good, not charity. As a result, more people signed up for assistance. While some people pick up their boxes at the center, volunteers deliver most of the food boxes directly to homes.

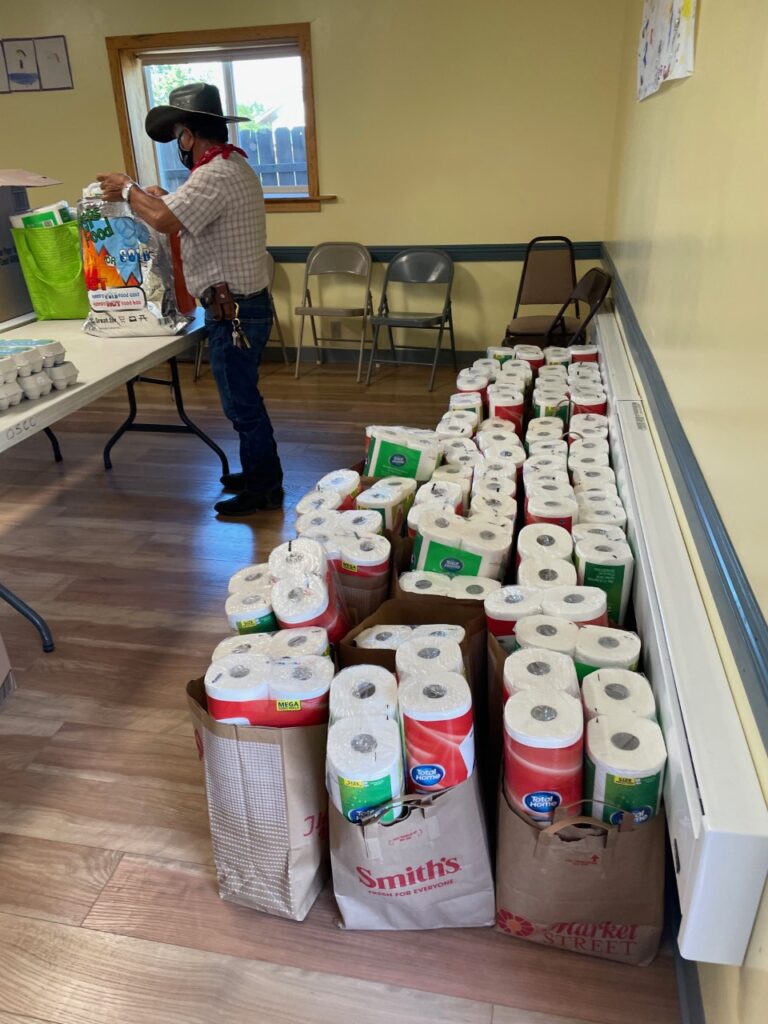

Essential supplies had never been a part of our food pantry, but literally overnight, locating items like sanitizer, face coverings, and toilet paper became very important. Tracking these items down through our existing networks and reaching out to newly emerging networks were both time consuming and expensive. Food shortages began to hit our area and meat started to be rationed as prices sky-rocketed.

Essential supplies had never been a part of our food pantry, but literally overnight, locating items like sanitizer, face coverings, and toilet paper became very important. Tracking these items down through our existing networks and reaching out to newly emerging networks were both time consuming and expensive. Food shortages began to hit our area and meat started to be rationed as prices sky-rocketed.

In addition to being the pantry, we stepped up as a transfer site for meals to children in those early pandemic days. The school district dropped off food to the center, meals were packaged, and members of the Ojo Sarco Volunteer Fire and Rescue Department delivered them to the children’s homes. By April and May of 2020, thousands of meals each month had been distributed from our site to children. By summer vacation in June 2020, the school district had staffed up to take over the meal delivery directly from the school cafeteria.

Among several pandemic high points, the most important was the overwhelming generosity of community members, the nonprofit community, state and local government. With critical emergency funding from the federal government and generous New Mexico foundations and individual donors, safety nets were quickly woven statewide to meet the challenges.

Public WiFi Hotspot

The Ojo Sarco Community Center is one of the first public wifi hotspots established by the Kit Carson Electric Co-op. Thanks to this longstanding partnership with our electric, telecom and propane cooperative, people are able to get online from the center and from our parking lot 24/7. Usage went up during the pandemic when school, work, activities and even government went online.

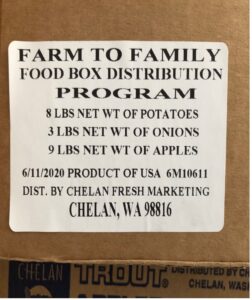

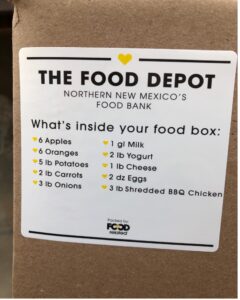

Farm to Family Program

By June 2020 the food supply began to get back on track and most important to our pantry was the USDA Farm to Family program. Fresh produce had been really scarce all through March, April, and May until the fourth Wednesday in June. For the first time, we had boxes of fresh, healthy fruits and vegetables to give to every household. Later boxes sometimes had eggs, milk, bread, and other items. The pantry volunteers were excited to see pallets of these boxes delivered and so were the households that received a box or two, depending on the size of the family.

By June 2020 the food supply began to get back on track and most important to our pantry was the USDA Farm to Family program. Fresh produce had been really scarce all through March, April, and May until the fourth Wednesday in June. For the first time, we had boxes of fresh, healthy fruits and vegetables to give to every household. Later boxes sometimes had eggs, milk, bread, and other items. The pantry volunteers were excited to see pallets of these boxes delivered and so were the households that received a box or two, depending on the size of the family.

The Farm to Family program was a win-win solution to help overcome pandemic disruptions in the food supply. Disruptions included labor shortages, transportation problems, covid outbreaks at meatpacking houses, and the shutdown of restaurants. Farmers gained contracts for their produce, and it went directly to homes with needs and services providers. These Farm to Family boxes continued for close to one year.

Based on the experience of our community, permanently funding the Farm to Family program is one of our top food security policy recommendations for Congress. The food was much fresher and tastier than much of the produce received in the past. These boxes often contained fresh carrots, similar to the ones I harvest from my garden. Carrots that taste like carrots.

Ojo Sarco Meets the Global Supply Chain

On the one hand is my home-grown carrot and on the other hand are the cases of canned carrots, other vegetables, and fruits imported from China that I had unknowingly been ordering. It bothers me that the United States Department of Agriculture, nonprofit food security programs from Feeding America on down, buy or otherwise obtain, and have us distribute food from China and other distant lands. I hold to the old-fashioned idea that the purpose of the USDA is to support U.S. agriculture while assuring that people in this country have access to good food.

In the business of international trade, food is treated just like any other item, from a cheap T-shirt to a child’s plastic toy to a car. Everything is just an item on a ledger. The difference with food is the inseparable link between food and health.

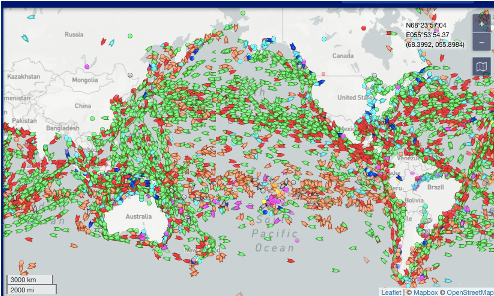

The pandemic has taught us that the global supply chain is an unstable fiction. This photo from the Marine Traffic website on October 22 visually shows a supply chain in free fall. Thousands of ships are adrift at sea waiting their turn at backed up at ports. Even when the cargo is off-loaded, there are not enough trucks or truck drivers to move the products. The system is broken.

What does the pandemic or global trade have to do with getting a tasty carrot in Ojo Sarco? It turns out that global supply chain failures have led to more availability of tasty, fresh carrots, and other vegetables in their season. Since the pandemic hit, more people have planted home gardens whether on a windowsill, in a pot or in the yard. The early disruptions in the food supply brought on a desire in many people to reconnect with their immediate environment. Both demand and prices for locally grown food are up. When safer-at-home orders went in place, restaurants were closed and people had to cook. Baking bread even became a fad.

Here in Ojo Sarco, two high school students signed up for community service at school and chose helping me set up the garden in the spring as their project. They are the new generation with their hands in the dirt, enjoying the taste of veggies they picked themselves. I am hopeful that the food system is leaving the worst of our times behind us and moving into the best of times with access to locally grown, healthy food available to everyone.

Carol Miller is a public health and social justice activist who has been living in a frontier mountain village in northern New Mexico for 45 years. In addition to being a New Mexico community organizer, Miller has worked at every level of government; local, state, and federal all the way to the White House. Miller is dedicated to geographic democracy, the principle that social and economic justice must extend to the smallest and most isolated areas of the country. No community left behind.