The Pandemic and Deaths of Despair in Western Pennsylvania

Editor’s note: The piece focuses on the Middle Suburbs because of the high rate of Deaths of Despair in these communities compared to much of the rest of the country. In the ACP typology, those counties come in just behind rural communities such as Graying America and Native American Lands. Ray Suarez visited Westmoreland County, a Middle Suburb in Pennsylvania, to get the on-the-ground view of the story.

When the pandemic hit, doctors, researchers, therapists, and law enforcement held their collective breaths. Deaths of Despair, the name widely used to describe early death due to suicide, substance abuse, and untreated mental illness had soared over the previous 25 years. What would a pandemic already bringing widespread social and economic impact to communities across America mean for people struggling with hopelessness, for people ready to give up?

The first signs were encouraging. Though the pandemic pushed down the accelerator on some of the drivers of Deaths of Despair like job loss, reduced social contact, and health problems, the numbers did not appear to take off. Laurie Barnett Levin, CEO of the Southwestern Pennsylvania Branch of Mental Health America, feared the worst, yet early on it didn’t seem to be materializing. “We really thought that as a result of the pandemic we would see a huge spike in deaths, deaths because of suicide. And that didn’t happen. And we couldn’t figure out why.

“And some of the hypotheses are that during the pandemic, people were sequestered together. They couldn’t go out, they couldn’t do things, and in a strange sense that was a protective factor because they were with other people.” Suicide is often carried out in solitude.

Barnett Levin said adjusting to challenge also acted as a helpful form of diversion. “Sometimes when you’re in the fight or flight mode, because it’s a crisis, your focus is on the crisis. It diverts your focus from what’s going on inside of you. You’re so busy in that survival mode: Your family. Where am I going to get my toilet paper? Where am I going to get food? You’re thinking more about those things. In a way it’s a kind of mindfulness activity. Your focus is more on those kinds of things, and your family’s all around you. And often Deaths of Despair take place when the person is alone, by themselves, and during the pandemic there was not that much alone time.”

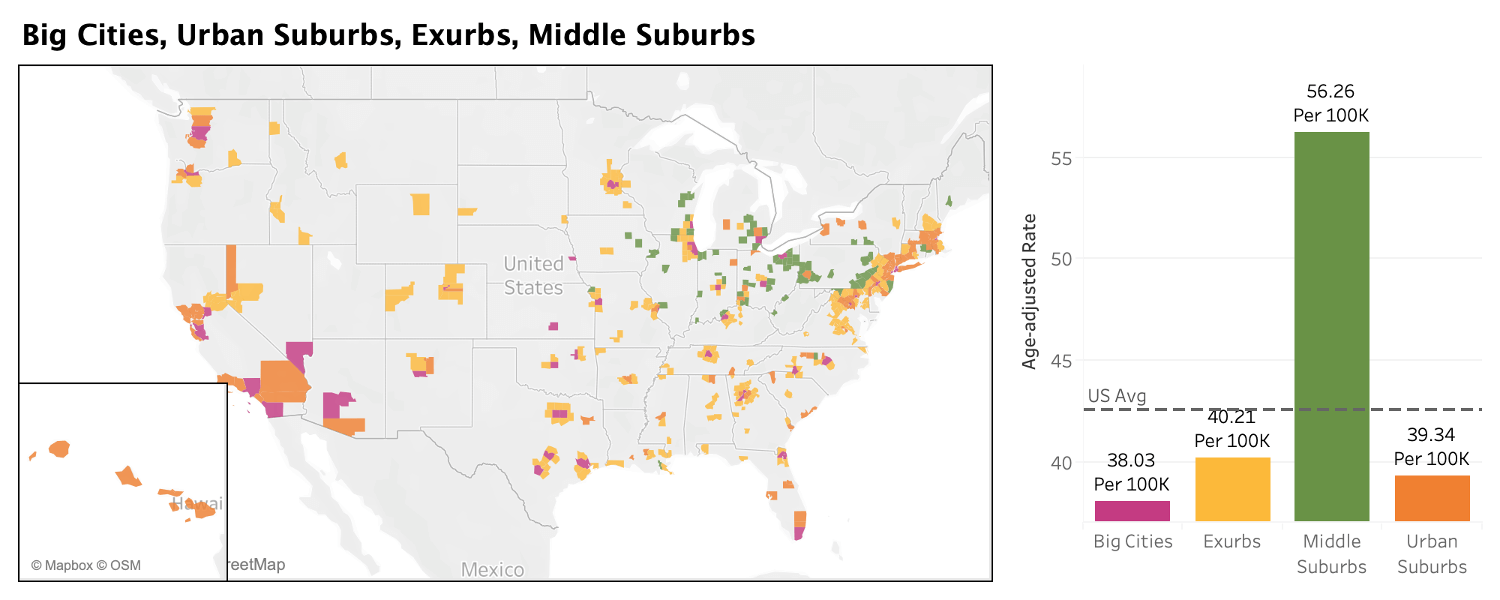

Even before the pandemic, the Middle Suburbs stood out in the ACP as the one metro-area community type that had high rates of Deaths of Despair. The figures in those counties were much higher than the numbers in the Big Cities, Exurbs, and Middle Suburbs. The last two years have only made the situation more challenging in the blue-collar communities around Pittsburgh and other places like them.

Microcosm of the Middle Suburbs

The social landscape, however, built in certain realities that leave Westmoreland County, like much of western Pennsylvania, vulnerable. In “Deer Hunter” country, as in so many places in the U.S., guns are a common tool for suicide, said Barnett Levin. “You put that together and homes where gun ownership is very common, multiple gun ownership is very common, and then you take the people that might be depressed, and I'm stereotyping, but men are often not the ones that reach out the most, and sometimes this is seen as a sign of weakness. So I think those are some of the reasons, and I think that it does follow national trends. There's certain groups, as you probably know, that are at risk, like veterans. The elderly are at risk, LGBTQ population, and they also have seen recently the rates are rising in African American young males.

“But Westmoreland County is a homogenous type of county (93.7% white in the 2020 Census). But we see the veterans. People who are experiencing financial hardships. During the last recession, when it first started, we were astounded because we thought we were going to see more death from suicide, and we didn’t. But a year or two later we did.”

After the first lockdowns, the pandemic devoured the rest of 2020, marched across 2021, and stretched into 2022. Anxious workers yearned for a return to their routines. Schoolkids attended on-again, off-again in-person instruction as the number of infections among young Americans rose, and the death toll continued its rise, with U.S. Covid-19 deaths likely to reach 1 million later in 2022.

Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, is a good place to watch for developments. Here, both the pandemic and Deaths of Despair have hit particularly hard. The county’s population has declined slightly during the last decade to just over 354,000. Deaths of Despair occur at a rate of 74.8 per 100,000 residents, compared to 64 per 100,000 residents in next-door Allegheny County and 52.8 per 100,000 in eastern Pennsylvania’s Bucks County. With a vaccination level below the state and national averages of just 57.5% fully vaccinated, 192.6 Westmoreland residents per 100,000 have died from Covid, compared to significantly lower 141.4 per 100,000 in Allegheny County, home to Pittsburgh.

The low rate of vaccination, as in counties across America, correlates with high support for Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election. The incumbent carried Westmoreland County by 28 points over Joe Biden. In Allegheny County, where the vaccination rate is higher and the rate of Covid death much lower, Joe Biden won by 20 points on his way to a narrow victory in Pennsylvania. In Westmoreland, vehicles flying Trump banners also carry bumper stickers cursing federal government infectious disease specialist Dr. Anthony Fauci, or proclaiming the driver’s unwillingness to be vaccinated, like a large drawing of a syringe covering a rear windshield carrying the slogan “I WILL NOT COMPLY.”

I spoke to psychiatrist Dr. Jonathan Metzl of Vanderbilt University, author of “Dying of Whiteness,” earlier in the pandemic, when its effects on Deaths of Despair were still unknown. Now, almost a year and a half later, vaccine resistance fell right into place with his wider set of conclusions about the politics of health. “Part of the issue for me is just how profoundly performative health politics have become forms of identity. In other words, to be a white, rural, Republican voter is to perform a particular set of health practices that involve arming yourself, and rejecting Covid science. This groundwork had been laid down for years. This groundwork was laid down in response to the Affordable Care Act, where to be a good conservative in your own community you had to reject your own free health care as a way of showing your tribal membership.

“What it means to be a white, conservative, rural voter right now is to reject Covid science, with profound implications.” Metzl worries about social cohesion, the willingness to trust research, and the many months of the pandemic yet to be gotten through. “The mistrust of traditional expertise is so great, and there’s a whole industry that’s popped up in its stead to fill that void.”

Largely rural and suburban, overwhelmingly white, hugging the median line for income in Pennsylvania and nationwide, it could stand in for a large number of hometowns across the mid-Atlantic and into the Great Lakes, home to a majority of the counties that make up the Middle Suburbs. In Westmoreland County, small communities cluster on two-lane country roads that suddenly jump up hillsides, make a quick semi-circular turn and plunge into an unexpected valley. It’s rural to the east, and more suburban in the western townships bordering next-door Allegheny County, home to Pittsburgh. The county seat, Greensburg, looks like a lot of places in the long arc of fringe metro area counties from inland New England, across upstate New York, into Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. The main commercial street features empty storefronts, pandemic-distressed businesses wrestling with reduced street traffic, closed and repurposed churches, and a magnificent 1906 courthouse stands at the summit of several major streets, giving it a commanding vista of the surrounding city.

To those working closely with at-risk Pennsylvanians, the early signs were not encouraging. Tony Marcocci, a detective with the Westmoreland County District Attorney’s office specializing in drug enforcement, saw problems emerge as the novelty wore off and the pandemic shutdowns and slowdowns dragged on. “Working in Drug Court affords me the opportunity to talk to a lot of people in recovery. When we were talking to people, not only in recovery but in active addiction, I noticed that everybody was going to remote NA meetings (Narcotics Anonymous, a 12-step recovery program). The meetings were on WebX or Zoom, individuals were losing their personal contact, which is so valuable in recovery, and oftentimes as a result, they were backsliding into using.”

From decades working with addicts, Det. Marcocci said not only were in-person meetings vital for encouragement and accountability, but also because they formed a social core around which informal links, connection to normal life, was built. “It’s more than just a meeting per se. So many individuals who attend meetings do stuff afterward, for lunch, for dinner, a movie, whatever. That was all taken away from them, that physical interaction was missing, so we saw so many people backsliding.”

The Economic Landscape

From economists Angus Deaton and Anne Case, whose groundbreaking work identified and measured Deaths of Despair as a social and economic phenomenon, to insurance companies to doctors to elected officials, the role of money has been watched closely as the death toll surged. Westmoreland County saw its fortunes decline like many other counties clustered in southwestern Pennsylvania, abutting other Deaths of Despair hot spots in West Virginia and southeastern Ohio.

The median annual household income, just over $60,000, is below both the Pennsylvania and national medians. The median age, at 47, is almost a decade older than the median age in the U.S. as a whole, clustering the county’s population heavily in the age cohorts particularly vulnerable to Deaths of Despair in Pennsylvania and the U.S., 45-54, and 55-64. Three out of every four housing units is owned rather than rented, with the purchase price well below the national average. Public transportation is sparse, leaving people without access to a car marooned in small communities far from shopping, medical care, employment, and school.

It’s a list of factors that are common in many Middle Suburb counties — and there are economic points as well.

The county’s main employers are no longer the coal mines, steel mills, and glass factories that built a secure blue-collar middle-class life. In 2022, the three largest employers in the county are Walmart, state government, and UPS, the parcel shipping service.

Thus, the pandemic brought a mixed bag for Westmoreland workers. Supermarket employees were classed as essential workers, shoppers retreating from retailers kicked parcel shipments into hyperdrive, and government workers were sent home in the thousands, and largely protected by collective bargaining.

Det. Marcocci said the economic trends had a strange, perhaps counterintuitive impact on the illicit drug economy. He says various kinds of state and federal emergency transfer payments put more money in people’s hands very quickly, and he saw the impact immediately. “Covid money was out there from the government. And in Westmoreland, used car sales skyrocketed.” The detective explained what seemingly unrelated data points meant to his work. “We border Allegheny county, which is Pittsburgh. For opiates, for sure, Pittsburgh is our source city. Most of the addicts travel to Allegheny County to get their supplies. With vehicles they were able to travel to Allegheny County more frequently, and now they had the money to obtain larger quantities.” Covid money, he said, spurred developments in the illicit drug trade. In Westmoreland County that meant increased access to methamphetamine, heroin, fentanyl, and prescription opioids.

Marcocci said more supply encouraged casual and marginal users off the sidelines. “The people that were trying to get clean or maintain cleanliness, people that were in drug court or trying to stay clean, saw this happening. So it’s in their face more. There’s more of a tendency to use when more people around you have it or are using. There’s more temptation to use.” Patterns of illicit drug use are shifting in response to purer, stronger drugs in the pipeline. Addicts who once favored one class of drugs and shunned another, think depressants versus stimulants, are moving to more than one class of drug as insurance. If a heroin user now fears overdose, he might take methamphetamine early the same day to hedge his bets against a dose that might otherwise kill him by suppressing heartbeat and respiration.

The Opioid Epidemic

Before the pandemic began, Pennsylvania’s governor, Tom Wolf, issued another disaster declaration, the fifth in a series, as opioid deaths spiked. Agencies across the state saw continued rises in the number of emergency uses of naloxone, a drug that heads off overdose deaths, and more babies born in the state’s maternity wards in withdrawal from drugs. These signs were abundant even as law enforcement across the state destroyed more than 250 tons of drugs collected in so-called “take-back boxes” installed around the state to keep prescription drugs from being diverted into underground markets.

Timothy Philips is executive director of the Westmoreland County Drug Overdose Task Force. He said he has also seen increased opioid supply, and family stress from the pandemic. “I think that just with the issues out there and people having problems and the uncertainty, it just sometimes seems so bleak. I think we're going to see an increase in behavioral health issues.

“I did a training with our Headstart staff. Headstart deals with little preschool kids. I couldn't believe some of the stories teachers were telling me about the behavioral problems and the issues with families and drug use and the kids and it’s just...heartbreaking. So I don't know if I'm just more aware of that now, or yeah, I mean we've provided the teachers with Naloxone and Narcan. We did a training for them too, because they have seen some overdoses with families in their facilities. Parents, grandparents using, whatever it was, and so yeah, I think it's going to even have a generational effect when we're talking about these young kids.”

The Mental Health Pandemic

Laurie Barnett Levin echoes concerns heard in other places in the country, and widely throughout Pennsylvania: The impact of Covid will continue well in 2022 and beyond. “We still think that we're going to see people who lose their lives to suicide increase. There’s a pandemic within a pandemic. That pandemic is the mental health pandemic.” She said the county’s available mental health service were already working at full capacity before the novel coronavirus came to this country, and everything has continued to get worse since. Barnett Levin noted that many industries have worker shortages right now, but “it was true in behavioral health before the pandemic. It has to do with salaries, it has to do with reimbursement, it has to do with paperwork, bureaucracy, so that you see that there are less people going into the field and you have people that are beginning to retire.

“In the more urban centers, you're more likely to find psychiatrists, but as you move out from the urban areas, you're less likely. And that is true in Westmoreland County, it's a big challenge to find psychiatrists who are the ones that are prescribing the medications. There's also nationally a tremendous shortage of child psychiatrists, and that's exacerbated in the more rural, semi-rural areas. Telehealth has helped with some of that, but it's still very difficult. There's waiting lists for people to get into treatment, and some of it has to do with people are increasingly now tending to their mental health, seeking services. The CDC did a study where there was a 30% increase in anxiety and depression brought about by the pandemic. So you're seeing more people trying to seek those services and less availability to have those services.”

Phillips said low pay and high pressure have combined to make the county’s efforts less effective. As part of a statewide effort to make drug counseling more available, he said, “Thousands of people in recovery were trained to be certified recovery specialists. Most of those people remain unemployed, or get into the field for a short time only to get back out because they can't make an adequate living. “You can't live on 10, 12 bucks an hour. And so we need to talk about developing the workforce, we need to be able to have the insurers pay for these services too. This is important stuff. It's about life and death, just like any other medical condition.”

Pennsylvania Studying Deaths of Despair

Befitting a place facing a particularly acute local version of a national challenge, Pennsylvania has devoted considerable resources to the task of understanding its causes, its scope, and its possible responses. Large insurers have teamed with Penn State University and state government to create a large and growing body of ongoing research into Deaths of Despair and their prevalence in Pennsylvania.

Dr. Lawrence Sinoway is a cardiologist, a distinguished professor of medicine, and director of the Penn State Clinical and Translational Science Institute. He has been studying Deaths of Despair for years, and is frustrated. For Sinoway, the social science and the research are solid, the medical evidence convincing, but his own profession is lagging behind. “Just the idea that if you talk to a psychiatrist about the definition of despair, they say it doesn't exist. There is no psychiatric equivalent of despair, the sense that it's greater than depression, it's constant impending doom. That doesn't exist necessarily in some of the medical stuff. So that is a major challenge. And what I see is a big problem, is what do you teach medical students about this? Right now we don't really have a curriculum. I'll give one talk with a couple of people. And wrap it around social determinants of health, but it's a much bigger issue.”

Highmark Inc., one of Pennsylvania’s major private insurers, does not need convincing. The company has funded extensive research into the chronic suffering and thousands of years of lost life accumulating across its coverage area. Sinoway knows there is a lot more research to be done, but said he has come away from the data sets convinced that if anything, the level of Deaths of Despair in Pennsylvania is underreported. “We took the electronic medical records or the claims data from Highmark and looked at 12 million people, and looked at the incidents of diagnoses associated with alcohol, associated with overdose, and associated with suicide.

“We found that this is exploding over the last 10 years. You can look at disease over time and show that things associated with it are increasing. You can show that from the early 2000s there is an increase in death and increases in diseases, so I believe it’s likely we’re underreporting both diseases and death.” Yet even a quarter century into the rapid rise of these deaths, Sinoway said, it still seems like early days. “When you talk to people in the state health department or in other hospitals and you talk about this despair, they say, ‘Oh, that’s a great name for it. I never knew that existed.’”

Integrating Social and Economic Data into Community Well-Being

Sinoway’s co-lead at the Penn State Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Dr. Jennifer Kraschnewski, told me more data is available on more aspects of America’s health than ever before, but they have not been as valuable or useful as they can be because they are not integrated. She said she is looking ahead to when “we can layer things that look at socioeconomic factors or variables, look at community aspects like organizations or churches in the community, looking at economic variables. And then combine these all together in a way where we can understand community risk factors and protective factors may look like, and how that interplays with the community’s health, not necessarily at an individual level, but more so at a population health level. How does that all work together and how do we make sense of things that you have to have a broader view to understand?”

At a moment in health care when so much is measured, and computers get more powerful by the day, we may also be inching closer to a time when the things we already know about towns and cities, counties and regions, can direct resources and help to head off Deaths of Despair before they happen.

Ray Suarez is co-host of the public radio program and podcast World Affairs, and covers Washington for Euronews. He is the author of three books on American life, most recently Latino Americans: The 500-Year Legacy That Shaped a Nation.