Colorado Exurb Newspaper Moves Residents With Its Mental Health Series

Sydney Chapin grew up in Highlands Ranch, a generally affluent bedroom community in Douglas County, Colorado, ranked as the state’s healthiest county in the 2017 and 2018 County Health Rankings. Chapin has struggled with anxiety and depression for most of her life.

Because she was raised in an area where having enough money is typically not a problem, she believes a preconceived notion exists that her mental health is supposed to be optimal — and fixable.

“There is an expectation to do well by everyone,” the then 19-year-old told a reporter in December 2017. “It’s hard to explain why I’m still depressed because to an outsider, I have everything. But it’s not about physical things — it’s completely about my mind.”

Chapin’s story kicked off Colorado Community Media’s eight-part series, “Time to Talk,” on the state of mental health in Douglas County, which with nearly 350,000 people is one of the nation’s fastest-growing counties, about 10 miles south of Denver.

Why We Focused on Mental Health Concerns

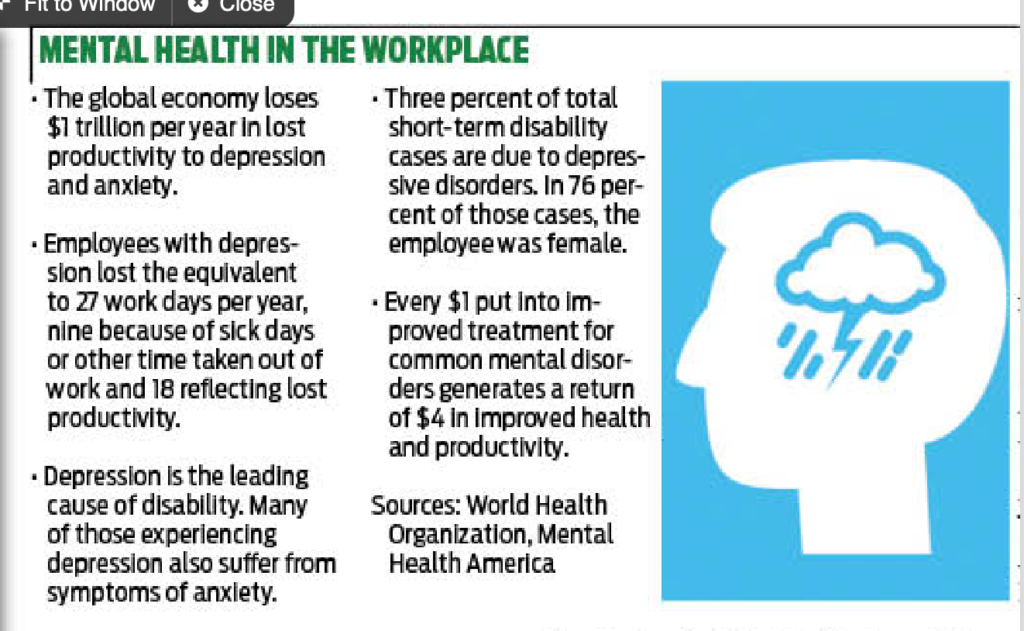

We spent a year exploring what mental health looks like in a suburban, affluent community, tackling all facets: youth suicide; addiction; depression among men, seniors, and mothers; the diminishing emotional intelligence of our youth related to the increasing use of technology and social media; the rising prevalence of mental health challenges in the workplace; the effects of mental illness on jails and the role of law enforcement.

We took on this issue as a cause because it resurfaced time and again during our weekly reporting of schools, government, and everyday happenings that make up the daily life of our county residents. And we thought, maybe, if we presented this well, we could help diminish the stigma associated with mental illness, help bring the issue into everyday conversation and make a difference through education, information and, most importantly, personal stories about the reality in our communities.

Alex DeWind and Jessica Gibbs were the lead reporters, juggling the intense work of the series with their weekly beat coverage. Reporter Nick Puckett came in at the end to help with the final installment. Because we’re a small staff, we can’t afford to take our reporters off their beats to solely pursue projects like this. The exceptional result was a testament to their passion and commitment to the issue. The team was rounded out by a page designer and myself as primary editor.

Our series was substantiated by national, state, and local research and data, such as:

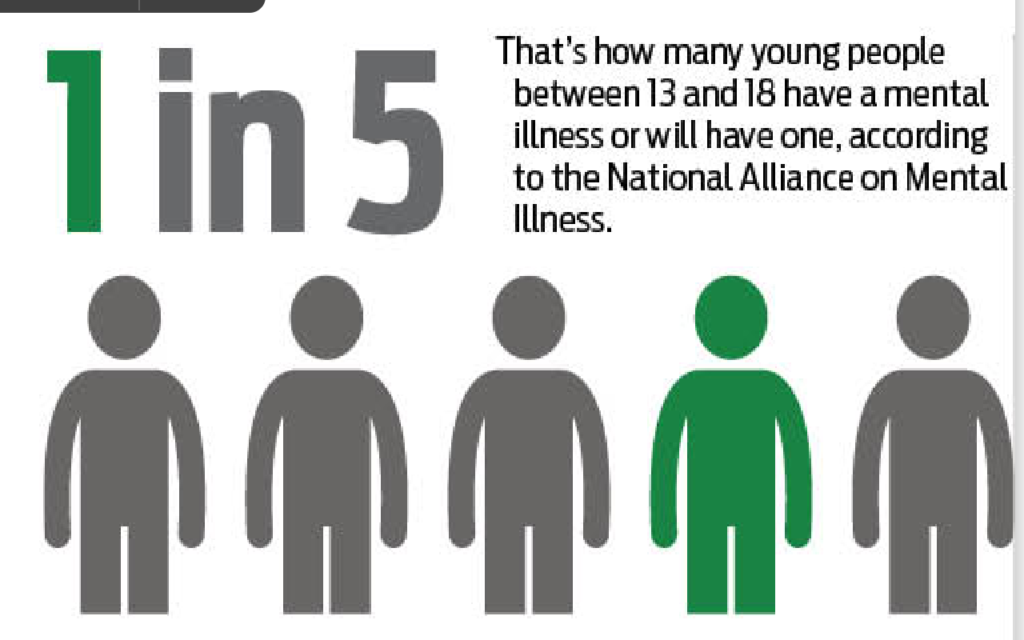

- One in five adults in the U.S. are living with a mental illness, yet 56 percent won’t receive the help they need.

- One in 10 women in Colorado experience pregnancy-related anxiety or depression.

- 50% of the average daily population in Douglas County Jail in 2017 were on psychiatric medication.

But what brought the issue home were the personal stories, which residents were willing to share with reporters who had built trusted relationships by being in their communities day in and day out.

Readership Swells

We deliver to 68,500 homes in Douglas County each week — three times the penetration rate of the area daily. The Time to Talk series page launched in April 2018 — a few months after we started the series — and saw daily strong readership. The landing page alone saw more than 40 views a day. Since April, the page has recorded 6,443 views. In the first two and a half months of 2019, some 400 viewers have gone to the series landing page, without any concerted promotion on our part. To compare, our Election 2018 landing page, which contained our most-viewed stories of all time, has had half as many visitors, and predictably, virtually all those views disappeared by mid-November.

Individually, the segments on the ties between mental health and addiction (which still pulls in a handful of views a week) and the effect of mental health issues on the role of law enforcement garnered more than 1,000 views each. Stories on social media’s impact on student mental health and sexting also continue to draw readers.

In a time when the refrain most repeated is that newspapers are dying — and the shrinking numbers of newsroom reporters, readers, and papers certainly support that —many small-town, community newspapers like ours, particularly those in rural areas, are holding our own. It isn’t easy: The struggle to maintain readership and advertising revenue is never ending, requiring innovative print and digital marketing strategies and a continual reassessment of coverage to ensure our lean staffs are meeting readers’ needs.

Still, more than 150 million people are informed, educated, and entertained by a community newspaper every week, according to the National Newspaper Association’s website. There are good reasons for this: The pages of local newspapers remind us of the importance of participating in democratic processes, and changes that — to be made — need our passions. Our mental health series was an example of such community engagement.

Wider Community Impact

Near the series’ conclusion in November 2018, a reader sent this email to one of our reporters:

“We feel that you really understand our community and the issues that matter. Unfortunately, people in our community are sometimes afraid to discuss the important topics because they fear being judged, but your articles help to initiate conversations and make people feel less isolated. Not only are you doing excellent reporting and sharing information, but you are bringing our community together and helping people see different perspectives.”

When we’re at our best, that’s what community newspapers do: present different perspectives that can bring communities together.

During our reporting on mental health, for example, we held two community forums to further the conversation beyond our newspaper pages. We teamed with Douglas County Libraries and the Douglas County Mental Health Initiative, a unique partnership of private and public agencies and faith-based organizations dedicated to identifying gaps in mental health resources and creating programs to fill them.

The first forum in April 2018 focused on youth, the other in November on maternal depression. Well-known mental health advocates and local residents shared their stories. About 50 people, mostly parents, women and older residents, attended each forum. We live-streamed the forums on Facebook to engage a larger audience, pulling in more than 3,000 viewers altogether, according to metrics numbers.

At the end of the second forum, several audience members asked when the next one would be and suggested focusing on the pressures teenagers face. Several city and county officials have suggested discussing civility. We are considering both ideas — it’s a matter of resources for us.

Evaluating Our Coverage

Did we accomplish what we set out to do with “Time to Talk?”

Feedback from readers, community leaders, and mental health leaders showed that it had sparked conversations about mental health in the community. Barbara Drake, the county’s deputy manager who spearheaded the formation of the Mental Health Initiative, publicly stated she believes the series contributed to the lessening of stigma about mental health in the county over the past year.

Drake believes the series’ specific focuses on men, seniors, and other demographic groups gave everyone something they could relate to, and the information and personal stories helped normalize the idea that people need mental health help to maintain physical health.

“Anti-stigma efforts help people to be more comfortable seeking behavioral or mental health treatment for themselves or their children,” she said. “Community newspapers and the library are the perfect place for people to get this information as they both represent where people go for unbiased and helpful information. They reach wide audiences of many types of people and they both bring credibility to the issues raised. This would not be the case if we left education and anti-stigma efforts only to the mental health professionals.

“I think this has been the beauty and benefit of your series and public forums. You’ve presented a lot of points of view, a lot of versions of what mental health issues look like, how it touches people in our community, where people can go to get help … how people can think about mental health needs in a more normalized way,” Drake said. “This is huge…. I suspect that for everyone that attended these forums or read the newspaper articles, there was at least a ten-fold impact of who people talked with (other community members) after attending or reading the articles….In a county that often struggles to talk about mental health, these avenues (forums and articles) have brought the topic to light in Douglas County.”

Journalists’ Key Learnings

Our team learned so much in reporting this project. Those insights included:

- A community with a high quality of living and wealth doesn’t mean its residents are immune from mental health challenges — the pressures to keep up with peers, to be high achievers, to pretend everything is OK even when it isn’t for the sake of image — is intense. And having a high level of education and financial resources doesn’t make navigating, understanding, or accessing a complex mental health system any easier.

- Younger people are more open about their mental health than older generations: They are more willing to share their experiences — which could portend a lessening of stigma.

- People living with a mental health condition are incredibly resilient: Most don’t give up and still find ways to care for the people around them despite their internal struggles.

- Solving this growing public health issue will require a concerted effort on the part of community and government leaders, along with the private sector. Gaps in care are huge, the need is dire, but there is a severe lack of money, resources, and coordination.

When we started this project, we knew the statistic: 1 in 5 people across this nation are living with a mental illness. That means we all know someone who is struggling. These stories, we hope, have reminded us that we can’t build community without knowing, learning, and caring about each other.

Ann Macari Healey is executive editor of Colorado Community Media, which publishes 18 weekly newspapers and two monthlies in the Denver metro area. She and her husband, Jerry Healey, have owned the papers since 2012. Five of the weeklies are more than 100 years old.

Ann Macari Healey is executive editor of Colorado Community Media, which publishes 18 weekly newspapers and two monthlies in the Denver metro area. She and her husband, Jerry Healey, have owned the papers since 2012. Five of the weeklies are more than 100 years old.