How a Native American Land Community Is Dealing with Drought and Poisoned Creeks

If you ask Juanita Crasco about the historic and unrelenting drought where she and her husband live and ranch on the Fort Belknap Reservation in northern Montana, she’ll talk about her apple tree.

“See here? I have a picture ready. You see how it’s just loaded with apples?” She took that photo on her iPad in 2021 and then drove roughly four hours to see her daughter in Browning, Montana, on the Blackfeet Reservation. When she returned two days later, all those apples were gone, decimated by grasshoppers. “They were so bad that year,” she says. “We lost a hundred percent of our hay crop. A hundred percent.”

Grasshoppers can’t control their body temperature and they need heat to thrive and reproduce. They like wide-open, hot fields and that’s what they got that year at the Crasco Ranch, which sits on the land Jake Crasco’s family was allotted by the federal government. Jake, 70, is enrolled Assiniboine-Nakoda and the third generation to ranch here. Juanita and Jake wanted to celebrate reaching 100 years on the original Crasco allotment, but that was the same year they lost their hay, “and we were too busy dealing with everything,” says Juanita, who’s Aaniih-Gros Ventre and grew up in Fort Belknap Agency on the northern end of the reservation. Her family also ranched, but eventually quit after years of costs far exceeding profit. In the last 20 years, the Crascos have had to reduce their cattle from a high of 1,000 to about 150. They attribute a lot of their decisions and their losses to a lack of water, but they’re not giving up, even in so-called retirement. “We’re still here. We’re not going anywhere,” Juanita says.

Fort Belknap is about 675,000 acres in Phillips and Blaine counties reserved for the Nakoda and Aaniih nations. Recent grant-funded imaging and analysis by scientists working with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, better known as NASA, focused environmental earth observation data on areas also struggling economically — including Fort Belknap. The hope was to explore the connection between environmental issues and the larger challenges facing communities of color. In Montana, the researchers found distinct areas of deforestation attributed to both fires and disease. They identified streams and creeks likely polluted by now-closed off-reservation gold mines that used cyanide leaching. They measured air quality degraded by wildfire smoke and mapped new roads in what had been wilderness. But among the most drastic findings was a loss of surface water. The data show nearly 60% of it dried up between 2017 and 2022.

Juanita Crasco took a look at that and said, “That seems low.” That's because drought and its effects have been part of what’s happening at Crasco Ranch for decades. Jake says the drought that started in 2000 “got worse and worse. But in 2002, that’s the first time I’ve seen this creek dry up since I was a little kid.”

The creek is close to their house and during the spring runoff of 2024, a season which also included a decent amount of rain in Montana, it was running again. Through a system Jake designed, water lines from that creek feed Juanita’s many pots, gardens, and even a greenhouse — a huge source of joy and pride for her. But in the pastures, the Crascos have learned the only way to stay in business is to rely on the water underground.

When the surface water previous generations counted on to water cows is no longer reliable, modern ranchers living in drought have to develop wells. That means paying others to find where and how to tap aquifers, and it also means getting in line — well-developers are in high-demand in Fort Belknap and its surrounds. The Crascos have had to develop wells on their own property, and also on their “summer grass” property 25 miles away where their cattle grazed during warmer months. On that land, leased to them by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Crascos applied for emergency funding to put in three wells in 2022. “It was either that, or lose our cows,” Juanita says.

They paid about $40,000 for the work on land they didn’t own and say they were told by an officer with the USDA they’d likely be paid back 90%. Afterward, a letter they keep in organized files in their house shows they were denied any reimbursement, citing missing environmental impact assessments they say they were not told were required. Because they could prove the new wells went in where old wells had been developed in the 1970s, the Crascos appealed the denial, finally winning at the state level on their third try, their documents show. But two years later, they’re still waiting for the money.

John Grande, president of the Montana Stockgrowers Association, doesn’t know the Crascos, but he knows the counties where they’re trying to make ranching work. “I heard that people in that neighborhood, that there were people who had grazing land with all kinds of grass, but there was no water and so people either had to drill wells or haul water up to these areas. And that becomes extremely expensive.” Grande grew up and ranches about three hours south of the Crascos, in Martinsdale, Montana.

Developing wells has become common as the ag world deals with drought, he says. The entire country’s cattle herd is at the lowest point since the 1950s. The best he can estimate in Montana is a 20% decline.

“Usually, when there is drought and cattle numbers are way down, the prices go up and what that should mean is cattle numbers should go up,” Grande says. “That’s not what is happening.”

That’s because people don’t have the resources to recover and increase their stock. “Ranchers need to heal up and pay for wells they drilled or hay they shipped in during the drought,” says Grande.

When drought covers a significant area — or when grasshoppers do — that also means buying hay from farther away. During recent years, Montana ranchers have tried to get hay from as far away as Kentucky, “and it may be cheap there, but by the time you truck it here, it is incredibly expensive,” Grande adds.

The Crascos don’t want to pour more money into acres they lease, so they made the decision last year to drastically reduce their herd. By keeping it to about 150 cows, they can keep them on their own land year-round and water them with current wells or ones they can develop without jumping through governmental hoops.

And they are getting older. Juanita has fibromyalgia. Jake essentially broke his back in an ATV accident in 2022, though you can’t tell from the way he is still doing everything that needs to be done, including firing up the generator that runs the pump on his newest well. In the winter, he has to still get out to this pump house and make sure the water will flow to stock tanks. And he still has to chip out the ice until he can afford new insulated tanks. That’s what he plans to buy if and when his reimbursement from the state arrives.

Standing in his driveway, he says, “I’ll take a hard winter any day. At least you know it’ll end. With the drought, you’re just never sure.”

Poisoned Waters

Other findings from the NASA-funded grant, “Environmental Injustice and Deaths of Despair: Lessons from Montana’s Tribal Lands,” focused on streams and creeks flowing into Fort Belknap, some identified as polluted by gold mines that closed more than 25 years ago.

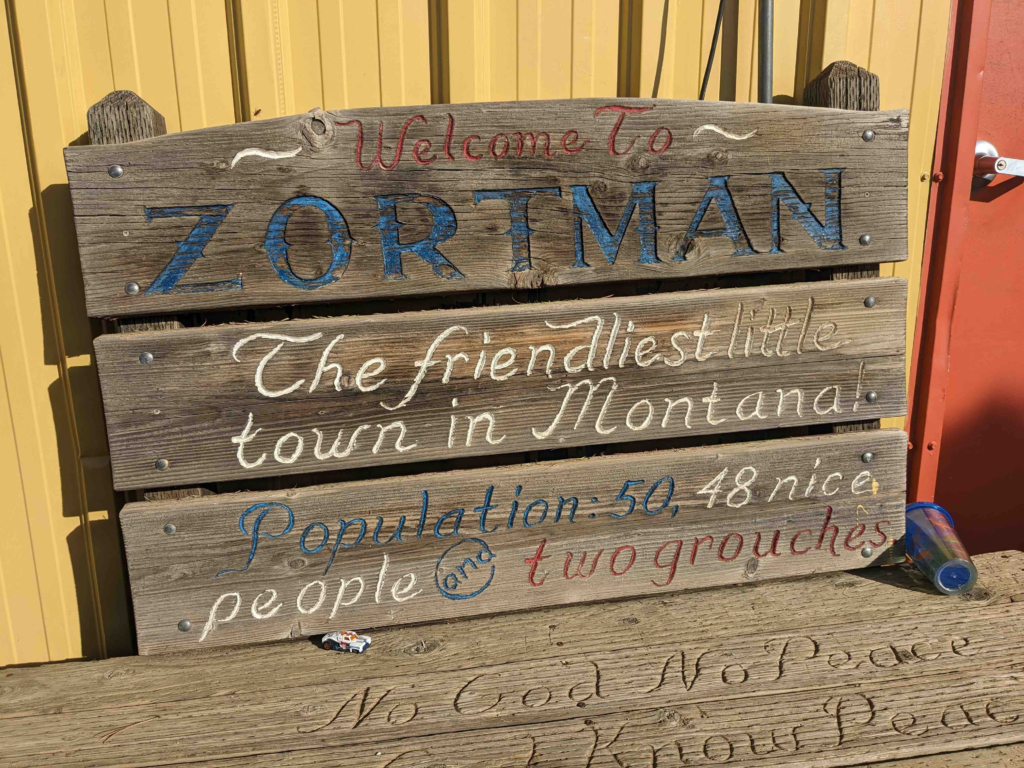

The Zortman and Landusky mines just south of the reservation’s boundaries were open-pit operations that essentially lobbed off the tops of low mountains and used a cyanide leach-pad method to dissolve rock surrounding precious metals. The company operating the mines, Pegasus Gold, ran them for 19 years, but closed them when it declared bankruptcy in 1998. Since then, the state has operated four treatment plants to mitigate water damage directly connected to the two mines. Taxpayer funding for those plants is well above $50 million so far.

The land the mines dug into was part of 30,000 acres the tribes were forced to cede because of discovery of gold in the Little Rocky Mountains, says Mitchell Healy, a water quality specialist who has worked for and represented the tribes on a multi-agency group monitoring damage from the mines for more than a decade. Healy, who’s enrolled Assiniboine, says the treatment plants at the mine sites are working, but they can’t account for spring runoff and other “high flow events.”

When those happen, he says, “it means untreated acid mine drainage water is bypassing the treatment plant and flowing onto the reservation, leading to years of iron oxide staining of bedrock, aquatic life and fish disappearing, the loss of beavers. And all of that impacts our culture.”

Part of his job on the working group is to identify these issues and help state agencies find solutions. “It seems hopeless at times,” says Healy, especially when he’s trying to explain to tribal leadership and others who never condoned the work of these mines that current science, technology and funding aren’t up to the job of stopping the problems at their source.

Wayne Jepson, also part of that working group, has been working on the damage from the Zortman-Landusky mines for decades as a hydrogeologist for the Montana Department of Environmental Quality. He started evaluating what was happening at the mines in 1992, when they were still operating. The water treatment plants he helped design will need to operate and undergo updates for many generations to come. And still, he says, “from day one, I told people this isn’t the final solution. More improvements to water treatment systems may be needed. Pretty much every spring, we’ll get a major snowmelt or rain event, and the water may still carry dissolved iron downstream.”

Healy, Jepson, and others in the group continue to come up with possible fixes, most of them grant-funded. One recently approved will treat the acidity levels of high-flow water, raising it to neutral and allowing dissolved metals to drop out as sediment. It’s worth a try, “but until this project is done and used, we don’t know if it will be successful,” says Healy.

The constant, says both Healy and Jepson, remains dealing with a long-ago decision to allow for this kind of extraction in Montana. “The main issue is open-pit mining — it’s mountain-top removal,” says Jepson. “You go from having a mountain to having a hole in the ground. The amount of rock removed and that’s now exposed is enormous.”

Reporting contributed by Lee Banville. Both Jule Banville and Lee Banville are professors of journalism at the University of Montana.