In a Coastal College Town, Progressive Takes on Different Meanings Over Generations

When you Google “Arcata, CA,” you will see us (pop. 18,178) on countless lists of America’s “best hippie towns.” You will read: “Arcata is a small university town…well known for its hippie counterculture, progressive politics, and vegetarian restaurants.” What likely follows will be something about cannabis cultivation, the most recent extraction industry Humboldt County has become known for. (Humboldt County is classified as a College Town in the American Communities Project).

This progressive place, however, was not the Arcata previous generations knew. It is a reality that dedicated individuals, many of whom came to attend Humboldt State University (HSU), helped to create. Now, some of these same leaders continue to push the community’s progressivism into the future as Arcata reckons with California’s housing crisis, climate change, and inequity. Increased attention has turned to racial inequity since the murder of a Black student leader, David Josiah Lawson, in 2017. More than four years later, he and his loved ones still have not seen justice.

In August 2019, I moved home to serve my rural hometown. As a senior at Brown University, I became connected with an amazing organization called Lead For America (LFA), which has a vision of building strong and loving communities across the country by placing young leadership and homegrown talent into the local governments, agencies, and organizations working on the nation’s most pressing challenges.

From Mining Outpost to Timber Town to Hippie Haven

Upon arriving as an LFA Fellow in the Arcata City Manager’s Office, welcoming mentors lent me many local history books that bettered my understanding of our unique corner of the world.

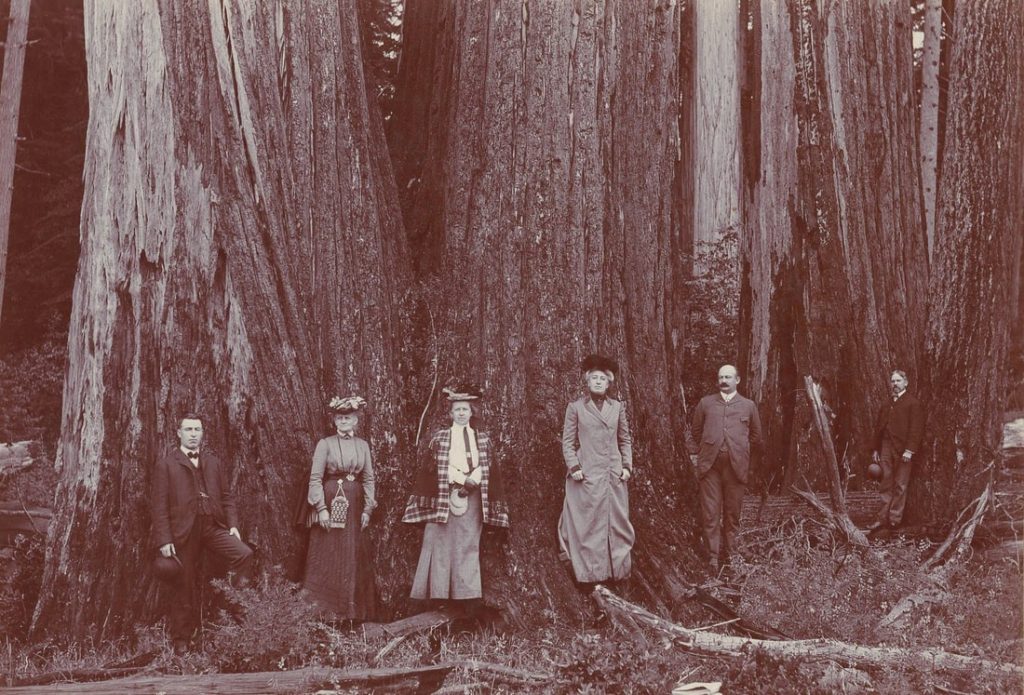

California’s far North Coast remained untouched by colonization longer than most of North America. The Wiyot people, who have inhabited what is now called Arcata since time immemorial, refer to this spot bordered by Humboldt Bay, the Mad River, and the hills of redwood forest as “Goudi’ni” –– meaning “over in the woods” or “among the redwoods.”

In the spring of 1850, a group of white settlers loaded onto ships in San Francisco (about five hours drive time south) and made the voyage up to Humboldt Bay. With six major rivers –– the Mad, Klamath, Eel, Trinity, Van Duzen, and Smith –– flowing through the region, the area was prospect-filled. Arcata was founded as a gold mining outpost. Between 1850-1860, the Wiyot tribe’s population fell from 2,000 to under 200.

Soon, Arcata turned to the redwood trees on its hillsides to sustain its growth. The “wild west” mentality of the newly formed State of California and the corporations that flocked to buy up these forests ingrained in Humboldt County and Arcata a very different culture than the environmentally-minded community of today.

Meeting Three Changemakers

In speaking with three mentors who helped guide the community through the changes of the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, I learned how these leaders’ re-envisioning of Arcata created the community I grew up in. In turn, our conversations have shaped my service throughout my fellowship, helping me to understand how young people stepping into leadership can be most useful.

Wesley Chesbro

Following an upbringing in Southern California, Wesley Chesbro was dropped off near the edge of HSU’s campus in 1969 by a truck driver who told him, “There aren’t many hippies who live in this town, but they all live there” –– pointing to a communal living house. Chesbro’s memory illustrated to me how different Arcata was in the late ’60s; the city I grew up in and serve today has hillsides scattered with residential communes. He knocked on the door, and some of the people inside became fellow activists and friends still today.

In 1974, Chesbro ran for Arcata City Council, three years after the voting-age change from 21 to 18. On the night before the election, he found HSU’s campus thoroughly flyered by conservative mill owner Robin Arkley, who was vehemently opposed to the idea that the newfound voice of younger students in Arcata would elect the two liberals running. The flyers read, “This isn’t your community…You shouldn’t determine the City’s government.” Both candidates were elected to Arcata’s five-person City Council the following day, and Chesbro went on to represent the North Coast in the California State Assembly for 27 years.

Alex Stillman

As part of the first liberal majority in Arcata in 1974, Chesbro joined Alex Stillman, the City’s first female representative. When she was sworn in as the first woman on the Arcata City Council in 1972, she was an HSU student, a wife, and a mother of two.

This revolutionary Council created some of the community’s most renowned institutions, including:

- the first public transportation system,

- the Open Door Clinic (“just a little hippie clinic” at the time which now serves families through seven locations), and

- the Arcata Marsh & Wildlife Sanctuary (Arcata’s innovative wetlands system sewage treatment plant).

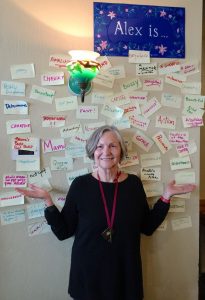

Connie Stewart

Connie Stewart, raised in New Jersey and San Jose, came to Arcata in 1984 at age 18 with a year’s supply of tampons, not knowing where she would buy them in her rural college town. At the time, Stewart was one of 63 Black students at HSU. As she remembered with a slight laugh, “There were like three of us in the dorms.” In interconnected Arcata fashion, Stewart’s first political job in Humboldt County was working for Wesley’s campaign for County Supervisor. In 1996, Stewart became the first Black woman elected to the Arcata City Council.

How the Three Are Active Today

Stewart serves as Executive Director of initiatives for the university, having recently left her position as Director of the California Center for Rural Policy (CCRP) at HSU.

Stillman wears many hats in the community, including: President of the Historical Sites Society of Arcata, Board Chair for Godwit Days (a 26-year-old birding festival that brings hundreds to the Arcata Marsh & Wildlife Sanctuary annually), and Board Chair of the Fire Arts Center (a ceramics and fused glass studio with popular community classes).

Chesbro left Sacramento in 2017, returning to an Arcata divided by grief and anger after the murder of David Josiah Lawson. Galvanized by experiences of harassment and marginalization that Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) students shared in the weeks, months, and years following, Chesbro joined Equity Arcata — a racial equity organization that the City of Arcata and HSU support in partnership.

Today’s Struggles: Racial Inequity, Housing, Climate Change

HSU enrolls about 6,400 students, 54% of which are BIPOC –– designating it as a Hispanic Serving Institution and a Minority Serving Institution. In contrast, Arcata’s non-student population is 74% non-Hispanic white and less than 3% Black. Following Lawson’s murder, in 2018, Arcata’s neighboring Eureka NAACP chapter called on HSU to stop recruiting students of color until the university took anti-racist action to support BIPOC students.

Chesbro described HSU as an “incubator for change”— noting how its graduates have always gone on to change Humboldt County and the world for the better. However, rather than embracing students as leaders in progress, some Arcatans look upon HSU and its student body as a foreign entity. The flyers posted the night before Chesbro’s election show that the marginalization of the HSU student population can be traced back to a logging industry survival strategy that vilified conservationist students in the 1970s.

However, today’s dynamic is not only inherently racialized due to the demographic imbalance between student and non-student community members, but also heightened due to California’s persistent housing crisis. About 75% of HSU students live off campus, and Arcata has maintained an anti-growth disposition toward creating new housing even as the majority of residents (about 57%) overpay for housing (defined as monthly housing costs that exceed 30% of the household’s income).

To complicate the situation further, some of those in Arcata’s older generations who paved the way toward an environmentally progressive community are now vocal voices in opposing ideas for housing solutions. Over the last couple of decades, when planners or developers have used words like “high-density” and “infill,” residents have opposed projects that would create housing, increase walkability and bikeability, and support businesses en masse. Stewart shared her frustration with a community that sees itself as environmentally progressive yet is staunchly opposed to density in the city’s urban core. As she sees it, if the forest and farmland on either side of the city are to be protected, infill is a necessary tradeoff.

Today, Stillman personally manages more rental units in historic buildings than any other single individual in downtown Arcata. She stressed the need to maintain our current housing stock and ensure that all existing homes in town are used — a reality complicated by Arcata’s high percentage of absentee landlords.

Residents’ objections notwithstanding, the need for housing in Humboldt County is expected to grow. As populous centers south of Arcata face drought and wildfire, this region of coastal greenery is predicted to become a climate refuge. The 2020 California fire season provided a glimpse into this anticipated movement, as many (who could afford to) fled the air quality in the Bay Area for Humboldt County’s comparatively moderately smoky skies. California’s urban areas have also become unaffordable to those without six-figure salaries. Perhaps due to both environmental and economic migration, Humboldt has experienced a steady housing price increase since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Making Change Where You’re Standing

Chesbro and I have worked together in Equity Arcata since my fellowship began. Before the pandemic, our working group (one of eight operating in different policy areas) hosted potlucks to bring Arcata’s student and non-student populations together in conversation and community.

This is an urgent need as student retention rates fall. In September 2019, HSU enrollment was reportedly down by more than 1,000. This decline was projected to continue, and has steepened since the pandemic began.

With potlucks off the table during the pandemic, our group applied for and received grants from local funders (including the CCRP via Stewart) to host “Free Meal & Stuff Distributions” for students –– hiring BIPOC-owned restaurants and food trucks and accepting community donations to provide a free meal and bag of free home goods, toiletries, gift certificates, a welcome note from a non-student community member, and other cost-saving items.

The work of welcoming youth is crucial — for the safety of students, especially BIPOC students, and so that Arcata doesn’t become, in Chesbro’s words, “a group of aging ‘60s and ‘70s graduates.” Equity work, pro-housing decisions, and re-embracing change in the Arcata community are necessary steps toward extending that welcome.

As Stewart said, “The best thing you can say to someone in a rural community is ‘you belong here.’”

Gillen Tener Martin has been a Lead for America Hometown Fellow since 2019.

Gillen Tener Martin has been a Lead for America Hometown Fellow since 2019.