In an Evangelical Hub, Hometown Heroes Hold Up the Social Safety Net

Editor’s note: With funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a team of researchers from the University of Michigan and Princeton University developed a quantitative Index of Vulnerability to identify America’s most disadvantaged communities across health, income, and mobility. For several months, students were embedded in a subset of these communities to interview both low-income residents and community leaders about how their communities got by, and what solutions would make a difference. The index, interactive map, and first set of written takeaways will be released in mid-January. For more information, and to be notified when the index gets released, please email Kate Naranjo, knaranjo@umich.edu.

Just outside Manchester, Kentucky, a small town with about 1,400 people, we barrel up a hill on a dusty, dirt road, the gravel crunching and a rainbow of green flanking the narrow road. I am in a van stacked with freshly cooked and packaged meals for seniors. The lead volunteer informs me that he is the only one comfortable driving the van on our route — with steep turns up narrow hollers, washed out embankments, and no cell service. At each stop, my companion tells me if I should knock or ring, who will meet me at the door, how long I should wait, and if there are dogs. At our first stop, the client welcomes us warmly. We make a delivery. Twenty-four more houses to go.

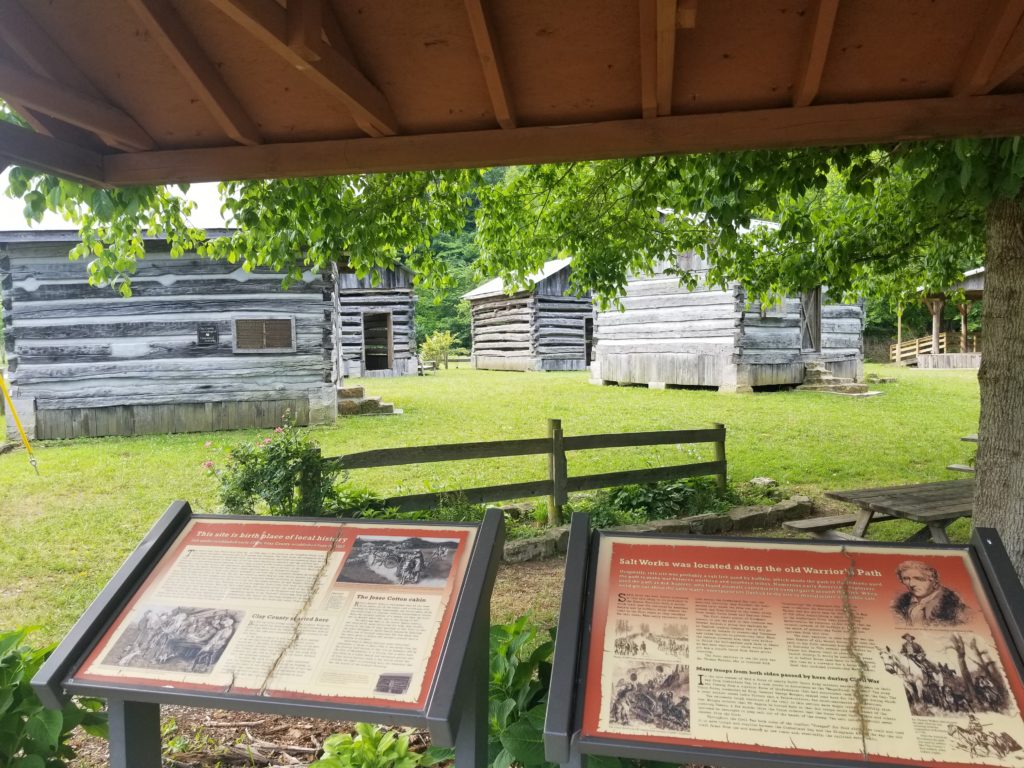

Earlier that day, I helped chop, pack, and clean at Clay County Old Timers, a senior services center. There were only three other volunteers that helped prepare nearly 200 meals. Always looking for ways to stretch a dollar, Carmen Lewis, the longstanding director, and her staff cook meals fresh and often barter with the food pantry. She, her staff, and volunteers make up one of many dedicated service provider teams scattered throughout Clay County, Kentucky, and other rural areas across the United States.

Providing social services in Clay County surely seems like a hero’s task when you consider the challenges of inadequate funding, limited staffing, and the time and expense of delivering resources to people spread across the county’s mountainous 470 square miles in the southeastern part of Kentucky.

Jobs that pay more than minimum wage, $7.25, are hard to find. The median household income is $26,400, and about 40% of the county’s approximately 20,000 residents live in poverty. Volunteers and faith-based organizations step up to work alongside state departments to fill the holes in the social safety net. (In the American Communities Project, Clay County is classified as an Evangelical Hub for its large number of religious adherents tied to evangelical churches.)

An All-Purpose Mission

Nestled in the Daniel Boone National Forest and surrounded by steep hills, lies Red Bird Mission. Founded in 1921, Red Bird Mission is one of the only health providers in the area. Today, the organization has ministries in almost everything — children and youth, parenting, clothes, food, farming, and health. Tracy Nolan, director of community outreach, says Red Bird tries to fill in gaps in health and service provision that other community players — like Daniel Boone Community Action Agency and the county Health Department — have not been able to address.

Clean water is a prime example. While water may typically be the government’s purview, in some rural areas, it is the property owner’s responsibility to get a water line to a remote part of the county. This is an exorbitant expense, often thousands of dollars, for families that are only making around $770 a month. To remedy this, in 2015, Red Bird Mission spearheaded a collaboration between the University of Tennessee, emergency services, and construction companies to get a source of clean water to the community.

Windshield Time Is Taxing

Transportation is a challenge for many of these workers as well as for their clients. When church groups around the country sent in millions of Campbell soup labels in 2003, Red Bird was able to purchase a fleet of vans through Campbell’s Labels for Education Program. However, the program was discontinued in 2016, leaving Red Bird with uncertainty. The staff at Red Bird are working hard to maintain the vans they have, but do not know where future ones will come from.

Ken Bolin, the lead pastor of Manchester Baptist Church, uses his personal vehicle to drive people in need to doctor’s visits, drug court appointments, funerals, and home. The pastor of Panco Community Church, Jerry Rice, drove a large church van up holler roads to take kids to Little League for 24 years. Getting a vehicle is just the first step to providing services — next up is having the time.

Our run to deliver food to 25 seniors took nearly three hours of driving, covering many miles of windy roads to places scattered throughout the county. We were on the short route. “Windshield time,” or time spent behind a wheel, takes a toll. People delivering hospice care or completing home visits to support new and expectant parents through the Kentucky HANDS program can spend five hours a day driving.

Desiring More Support

Christie Green, director of the Cumberland Valley Health Department, says she would love to apply for grants for staff support, but she just doesn’t have the capacity — in having staff to write the grant or in fulfilling reporting requirements. Green spends a lot of her time away from her desk in addition to her management roles. In fact, to get drug users to participate in their needle exchange, Green and staff went directly to drug dealers to ask where and when they would use a needle exchange.

Social service providers say what makes their daily work difficult are the lack of funds and an overworked staff. “I have all these big things going on and then little stuff kind of trips us up. We can’t be quickly responsive to things because we don’t have any discretionary funds to quickly move in one direction or another. And that’s pretty frustrating,” says Green.

There are so many daily to-dos that big-picture planning, such as obtaining grants and creating a vision, is on the back burner. Many service providers in the area echo this sentiment. These organizations need more funding for staff, investments in human capital and staff training programs, and follow-up with accountability measures and next steps. Funding for durable goods from the government or nonprofits, including vehicles or even printers, and not just to the programs the public likes, would free up valuable discretionary money for cash-strapped organizations. Green informs us that before our interview, instead of working a grant, she spent time changing a light switch because hiring an electrician would have taken too much money out of her budget.

Making Trade-offs Amid Loss of Workforce

The experiences of local service providers are not just anecdotal. Local money to fund social services has been eroding. Property tax revenue once abundant in Clay County, due in part to higher paying coal jobs, has dried up. Over the past 15 years or so, property tax money has shrunk to a fourth of what it used to be, and according to the county executive judge, Johnny Johnson, money from coal service tax has fallen from nearly half a million to a little more than $30,000.

No other industry has come in to replace the jobs lost. The working-age population has been thinning while the older population has been increasing. Residents 65 and older compose 15% of the county’s population; 22% of residents are under 18. Students who go on to college often cannot find a well-paying job back home. Clay County’s unemployment rate is 8.5%. However, community leaders say many residents have stopped looking for work, so this official number is misleadingly low.

To keep services afloat, city and county officials make difficult trade-offs, while at the state and federal levels, funding continues to be slashed. At the same time, government funding has a complicated history in Clay County. A common feeling among community leaders is that despite well-intentioned and significant efforts by government and community groups over many years, there has been little progress in curtailing poverty. Why is this? The most commonly cited barrier to reducing poverty in the county is the lack of jobs that pay a living wage. If you can’t fix that, some say, nothing else matters.

It is not uncommon for workers to drive an hour and a half each way to Georgetown or 45 minutes to London to find employment. To make ends meet each month, residents often double up with other households, barter labor, visit God’s Closet (a clothing ministry) or Red Bird for basic necessities, sell possessions on the side of the road, or pawn belongings.

How It All Works Out

Entire systems of service provision in Clay County are run by dedicated leaders and volunteers who deeply care about their community. But being stretched thin takes its toll and leaves questions about long-term sustainability. What happens if someone retires or gets sick? Community leaders think about succession planning, but put it off indefinitely because of all their other daily tasks.

In the meantime, community leaders — some natives, some transplants — keep on helping. These leaders share some characteristics — they are creative problem solvers, passionate about their work, and humble about their successes. It is doubtful that any of them would refer to themselves as a hero. Many believe God will provide a way to continue their work. That keeps them coming back, cheerful, and ready to serve.

As Carmen Lewis puts it, “If you are doing the right thing, usually God works it out. It’s just like Jesus and the fish. It’s like, ‘Huh?’ That’s impossible for that to have worked. But it happens all the time, and that’s the way we feel. You know, you try to do the right thing and do extra for people and just be good to people, and it always works out.”

Emily Miller is a second year PhD student in Population Studies and is pursuing a Joint Degree in Social Policy at Princeton University. Her research interests include how service providers function in rural areas and how to foster collaboration across sectors. She is also curious about how demographic characteristics and family expenses vary across rural, suburban, and urban areas. This past summer, she was embedded in Clay County, Kentucky. Her undergraduate degree is in Policy Analysis and Management from Cornell University, and she worked for two years at Child Trends before coming to Princeton and to this project.

Emily Miller is a second year PhD student in Population Studies and is pursuing a Joint Degree in Social Policy at Princeton University. Her research interests include how service providers function in rural areas and how to foster collaboration across sectors. She is also curious about how demographic characteristics and family expenses vary across rural, suburban, and urban areas. This past summer, she was embedded in Clay County, Kentucky. Her undergraduate degree is in Policy Analysis and Management from Cornell University, and she worked for two years at Child Trends before coming to Princeton and to this project.