In the Pandemic, Columbia Gorge’s Food System Mobilizes for Farmworkers and Native Americans

Editor’s note: The American Communities Project explored health and socioeconomic trends across our 15 community types in our first report in the fall of 2018, supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. We also took deep dives into five communities of different types, including Hood River County, Oregon, a Hispanic Center in the Columbia River Gorge region. While in Hood River, we met with Sarah Sullivan, executive director of Gorge Grown Food Network. In the post below, Sullivan shares an update on her community’s work.

Resilience. Never before has that word in Gorge Grown Food Network’s mission seemed so relevant: to build a resilient, inclusive food system that improves the health and well-being of our community.

Even before Covid-19, the Columbia River Gorge, 65 miles east of Portland, Oregon, 1 in 3 people worried about where their next meal would come from. In communities of color, hunger is even more pervasive: A survey by the Columbia Gorge Health Council found that 53% of farmworkers and 59% of Native Americans are food insecure. In the past nine months, many stakeholders have been coming together to support these two vulnerable populations.

Meeting Native Americans’ Needs

In March 2020, a group of 40+ agencies started meeting weekly to support the Native Americans living along the Columbia River. The group, which includes four tribes and representatives in social service, food access, and health care, provides Covid-19 testing, food, resources, counseling, child care, clothing, and any other needs.

Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest have fished for salmon, sturgeon, steelhead, and eel on the Columbia River for at least 11,000 years. On March 10, 1957, The Dalles Dam on the Columbia River closed its new floodgates, covering Celilo Falls, the center of the fishing traditions of the region’s tribes. The dams and warming waters greatly impact the number of salmon that are able to return to spawn, threatening the tribes’ primary food source and traditions. Today, “in-lieu” fishing sites along the river are home to hundreds of people who mourn the loss of Celilo Falls.

The Columbia River Intertribal Fisheries Commission (CRITFC) represents four tribes from Warm Springs, Nez Perce, Yakama, and Umatilla. When Covid-19 hit, CRITFC quickly enacted its Emergency Preparedness Plan and set up incident command. Buck Jones, a salmon marketing specialist, found himself delivering food and other resources to more than 250 families a week. Working with The Wave Foundation, partners assemble healthy food boxes with a focus on culturally appropriate food — local fish, wild rice, and bison — which is caught, grown, and processed by Native Americans.

Now, the network of agencies is embarking on strategic planning to move beyond emergency food access toward tribal food sovereignty and housing security.

Lobbying for Farmworker Health

When Covid-19 spread among farmworkers and employees at food processing facilities across America, leaders in the Gorge quickly formed a Migrant/Seasonal Farm Worker Health Initiative coordinated by The Next Door, a social service agency in the region. The multi-pronged approach includes six action committees focused on personal protection equipment, housing, food, health care, workplace safety, and communications. Committee members include Latinx health equity advocates, medical professionals, orchard owners, and social service providers.

Early in the pandemic, the group secured personal protection equipment for the 60,000+ farmworkers that pick and process fruit each year in the Gorge. The Columbia Gorge Food Bank, “Bridges to Health” staff, and the health department coordinated food delivery to quarantined families. The communication committee created eight culturally-specific Spanish language videos to help with Covid-related education that are now being used statewide.

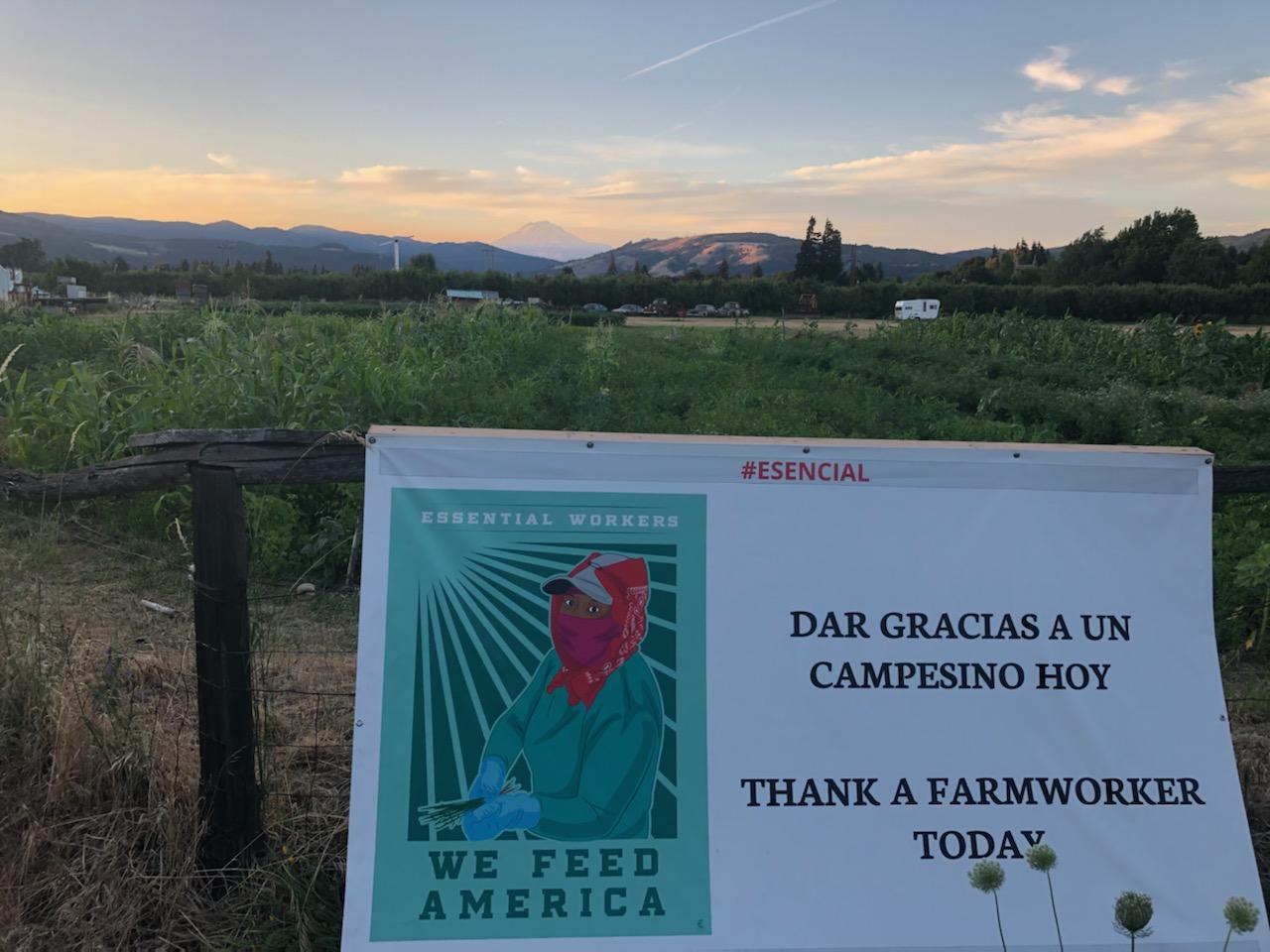

The “Esencial” campaign thanked agricultural workers for their work. Banners were hung throughout the community, and community leaders published articles and spoke out on the radio about farmworkers’ challenges. They said what needed to be said:

- Farmworkers deserve adequate, safe, dignified housing not just now to enable social distancing, but always.

- Food system workers deserve hazard pay for putting themselves at risk for their jobs during this time as well as paid sick time so that they can stay home if they are not feeling well without facing financial ruin.

- They deserve fair living wages rather than “piece-rate” pay, compensation based on bins or pounds of produce that discriminates against elderly and disabled workers.

The Next Door and partners across the state lobbied for funding to support undocumented farmworkers, and the state of Oregon allocated $20 million for the Oregon Workers Relief Fund. Unemployed workers who do not qualify for unemployment insurance can receive up to $1,720: Now, more than 500 farmworkers in the Gorge have received this support. However, we recognize that achieving an equitable, fair food system will take a lot more work.

Providing Food for All

When the pandemic hit, Oregon Gov. Kate Brown declared farmers’ markets an “essential service” and critical food access point. This enabled Gorge Grown to open farmers’ markets earlier than usual in April 2020, despite initial pushback from some local officials and the health department concerned about any public events. With technical support from the Oregon Farmers Market Association, Gorge Grown staff developed an exemplary farmers’ market safety protocol that has now been replicated around the county.

Funders like Partners for a Hunger Free Oregon and the Northwest Farm Credit Services provided additional support for low-income SNAP (EBT) shoppers: SNAP participation increased by 118% compared to 2019.

For the first time, farmers came together to form an online local food marketplace, Gorge Farmers Collective. This filled a gap for some of our most vulnerable community members through a partnership with Providence Memorial Hospital Oncology in Hood River. Food-insecure cancer patients are given a “veggie prescription” from their health-care provider to order fresh, local produce online. Gorge Grown Food Network staffers provide recipes and support, and volunteers assist with the produce delivery. This program serves two purposes: increasing access to fresh, nutrient-rich food for those battling cancer and supporting a new farmer-led business enterprise.

When meat processing facilities started closing due to Covid-19 outbreaks, farmers like Dr. Karleen Swarztrauber of Tephra Farm found herself with animals ready to harvest and nowhere to take them. Michael Kelly of Treebird Farm had recently built his own butchery, and he agreed to buy Karleen’s hogs, then process and sell them for her. Treebird started aggregating other products, and customers enthusiastically signed up for grocery delivery. In October 2020, Treebird was able to buy a building to launch their new brick-and-mortar grocery store, providing a new sales outlet for farmers region-wide. Two meat producers in a rural area like Treebird and Tephra farm could position themselves as fierce competitors, but in coming together to market their unique products, they have both grown their customer base — and demonstrated resilience.

* Some individuals living in the Columbia Gorge identify as Latinx, while others identify as Latino/a, Hispano, Hispanic, or with their country of origin or lineage.

Sarah Sullivan is executive director of Gorge Grown Food Network, a nonprofit working to build an inclusive, resilient food system in the Columbia River Gorge of Oregon. Most recently, Sullivan and her staff launched one of the most robust Veggie Prescription (Rx) programs in the nation across five counties in two states with 40 health care providers. More info can be found at http://www.gorgegrown.com/foodsecurity/

Sarah Sullivan is executive director of Gorge Grown Food Network, a nonprofit working to build an inclusive, resilient food system in the Columbia River Gorge of Oregon. Most recently, Sullivan and her staff launched one of the most robust Veggie Prescription (Rx) programs in the nation across five counties in two states with 40 health care providers. More info can be found at http://www.gorgegrown.com/foodsecurity/